This collection includes a flurry of diagrams bringing regenerative aspects of sustainability to the fore. As usual, wading through the ever-persistent pillars models, now usually disguised as things such as “sustainable business innovation”. Is it just me, or is the management literature 20 years behind sustainability science?

Updating the collection of images describing sustainability.

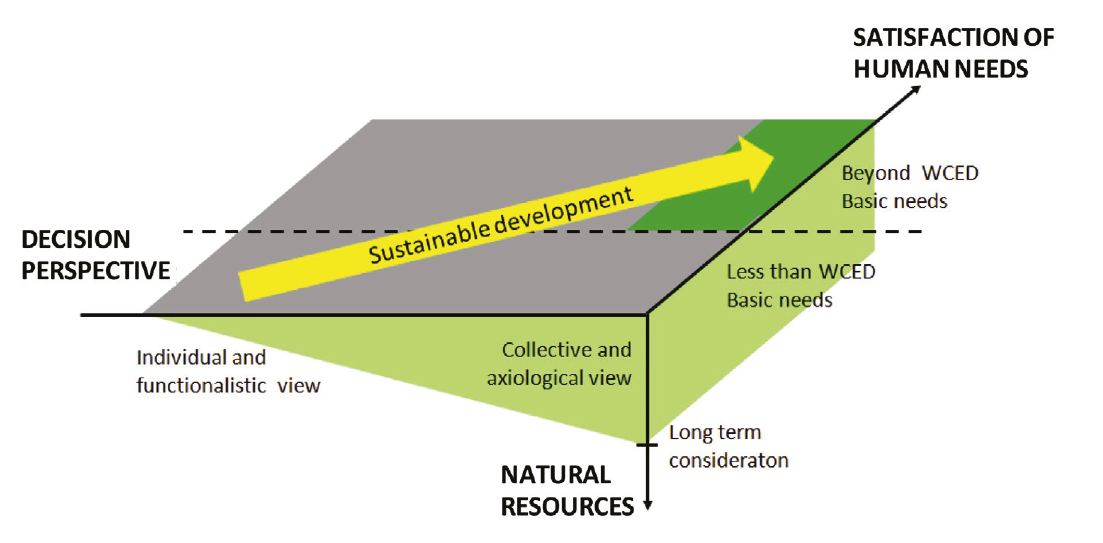

601. Axiological ramp (Bolis 2014)

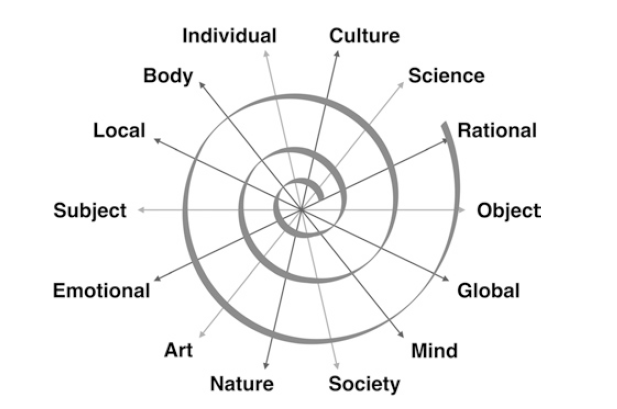

Decision perspective dimension: represents a continuum of scope to be considered in decision making processes, starting from individual and functionalist drivers and evolving to axiological drivers. In this dimension, it was considered that decisions can be made based on the goals and constraints of the individual, family, organization/community, state, continent or global society. At one extreme (individual and functionalistic drivers), the decision perspective is concerned with objective, rational, short term, restricted and problem-oriented issues. At the other extreme (axiological drivers), this perspective considers more subjective, emotional, long term, value-based, systemic and intergenerational aspects before reaching a decision. This latter decision perspective promotes initiatives that are based on social values, ethics, cooperation, equity and equality. In this dimension, the main question is: are positive and negative impacts for society considered in decision making-processes?

One of the dynamics that contributes to sustainable development is the positive relationship between the decision perspective and natural resources concerns. This can be considered reasonable, since axiological drivers for decision making mean that decisions are not based on the short term individual impact of resource

exploitation. Instead, this perspective ensures that future generations are also able to satisfy their needs using the natural resources available in their time.

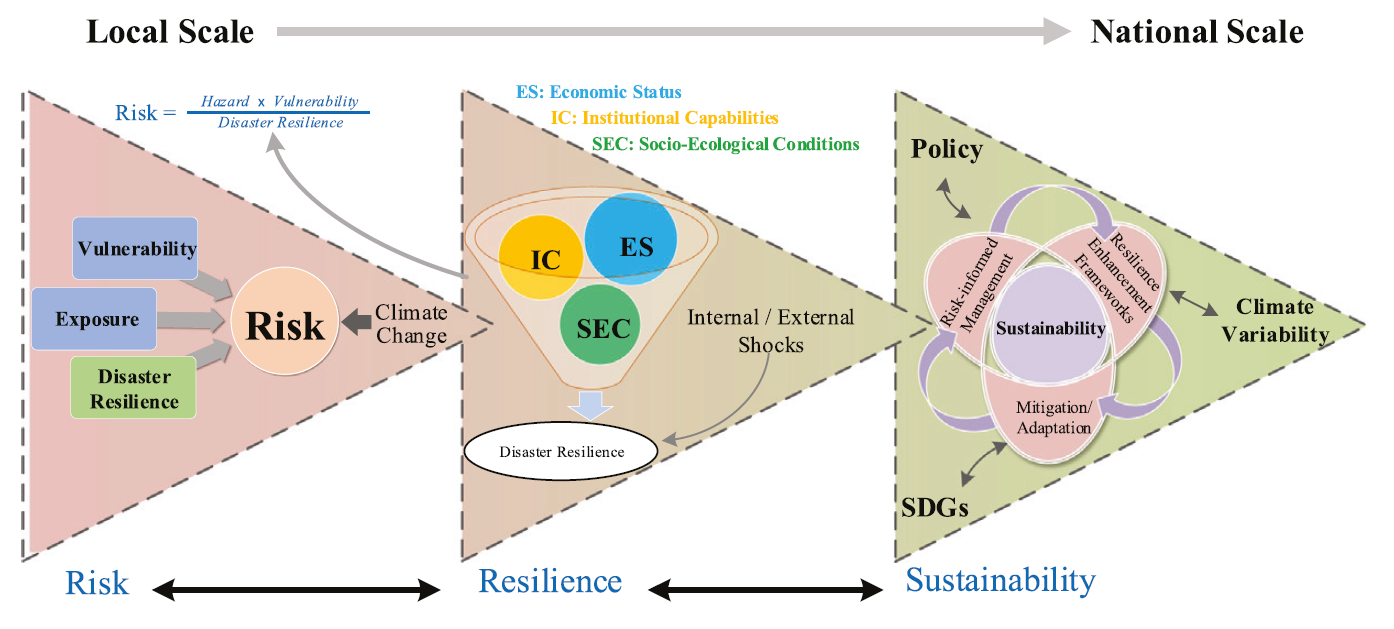

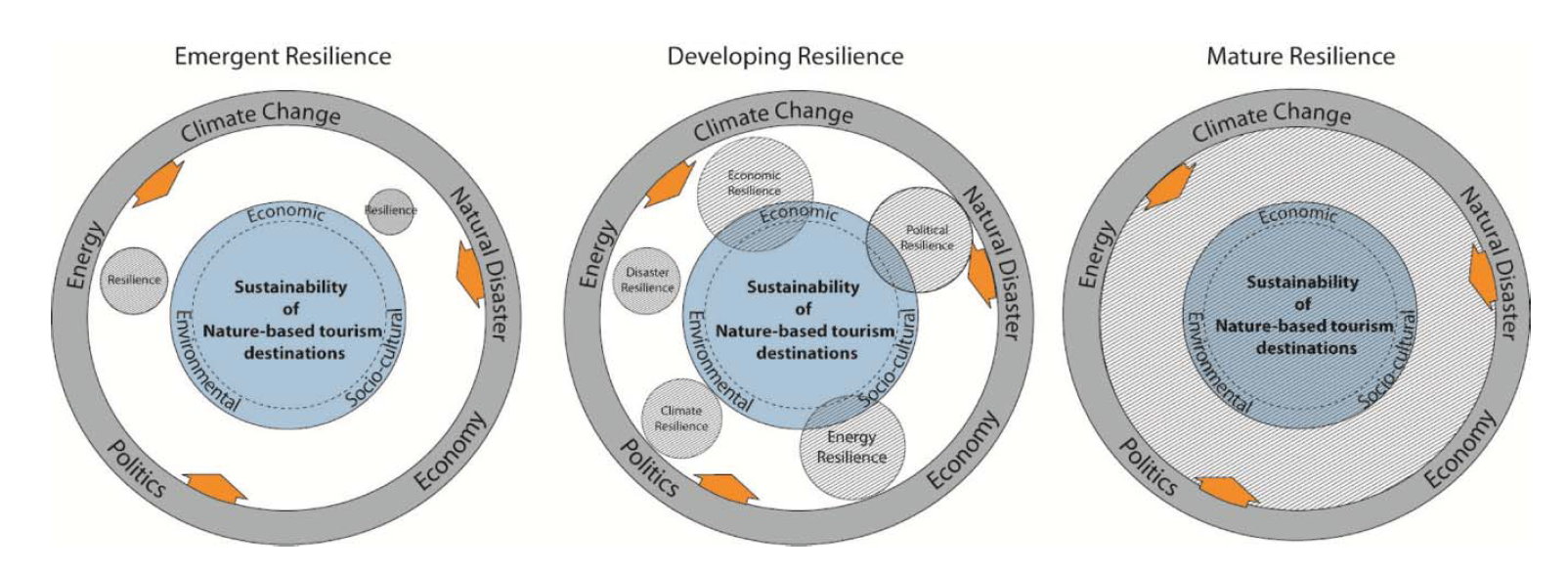

602. Risk assessment (RA) framework focusing on the risk-resilience-sustainability nexus (Sajjad and Chan 2019)

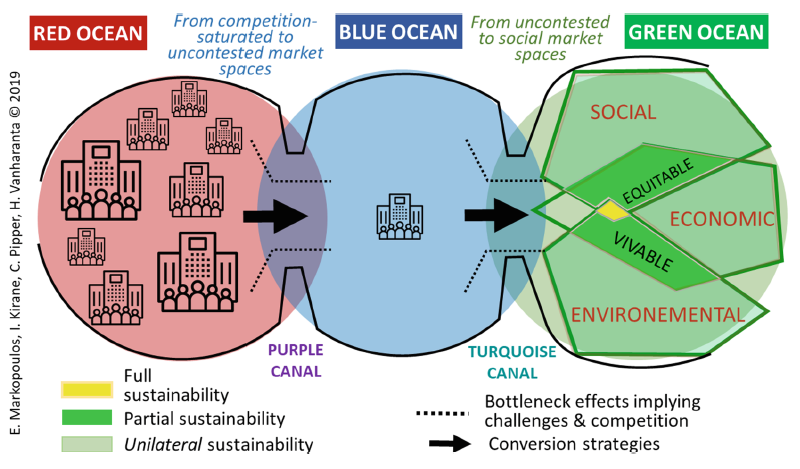

603. Green ocean (Markopoulos 2020)

The oceans transition process through the transformation canals.

The Green fuel required for an organization to reach Green Oceans through the turquoise canal is an everlasting resource that exists in every organization regardless its size, market or expertise. It is the knowledge of the employees which resides with an organization at no cost, enough to lead a green transformation. However the challenge is on the effective way of collecting, analyzing and utilizing such knowledge. Knowledge democratization is an approach to this challenge. No one knows where an idea can come from or what solutions can derive from the organization’s human resources by treating employees as capital assets and not as white- or blue-collar workers.

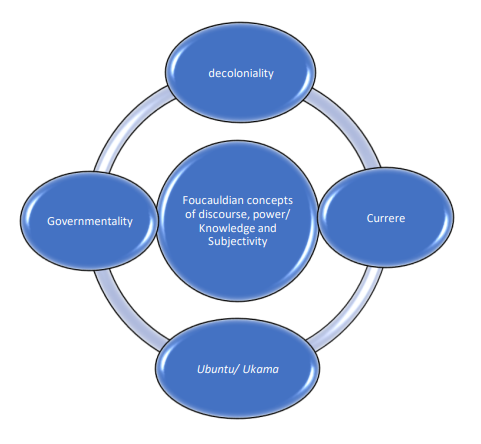

604. Southern environmentality dispositif. (Musindo 2022)

While decoloniality allows for the integration of cultural perspectives regarding the environment and further aids the emphasis on curriculum as a discursive process, Ubuntu/Ukama emphasises non-hierarchical power relations in human-nonhuman interactions and resource use. Discourse, power, knowledge, and subjectivity from a decolonial perspective allow for a critique of Western dominance to envisage a non-hierarchical form of power, a coexistence of knowledge and knowing subjectivity for re-existence. These concepts engender the ‘transformative vision of an alternative society’. Decoloniality then opens spaces for Ubuntu/Ukama. While decoloniality through the concepts of power, knowledge and being contains potentialities and possibilities for creating another world, it is when it is interpellated with Ubuntu/Ukama that decoloniality becomes a sound basis for re-imagining power, knowledge and being that promotes sustainability. Nature-culture binaries inherent in the curriculum are opposed by Ubuntu/Ukama.

605. Relationship with resilience (in nature-based toursim destinations) (Espiner 2017)

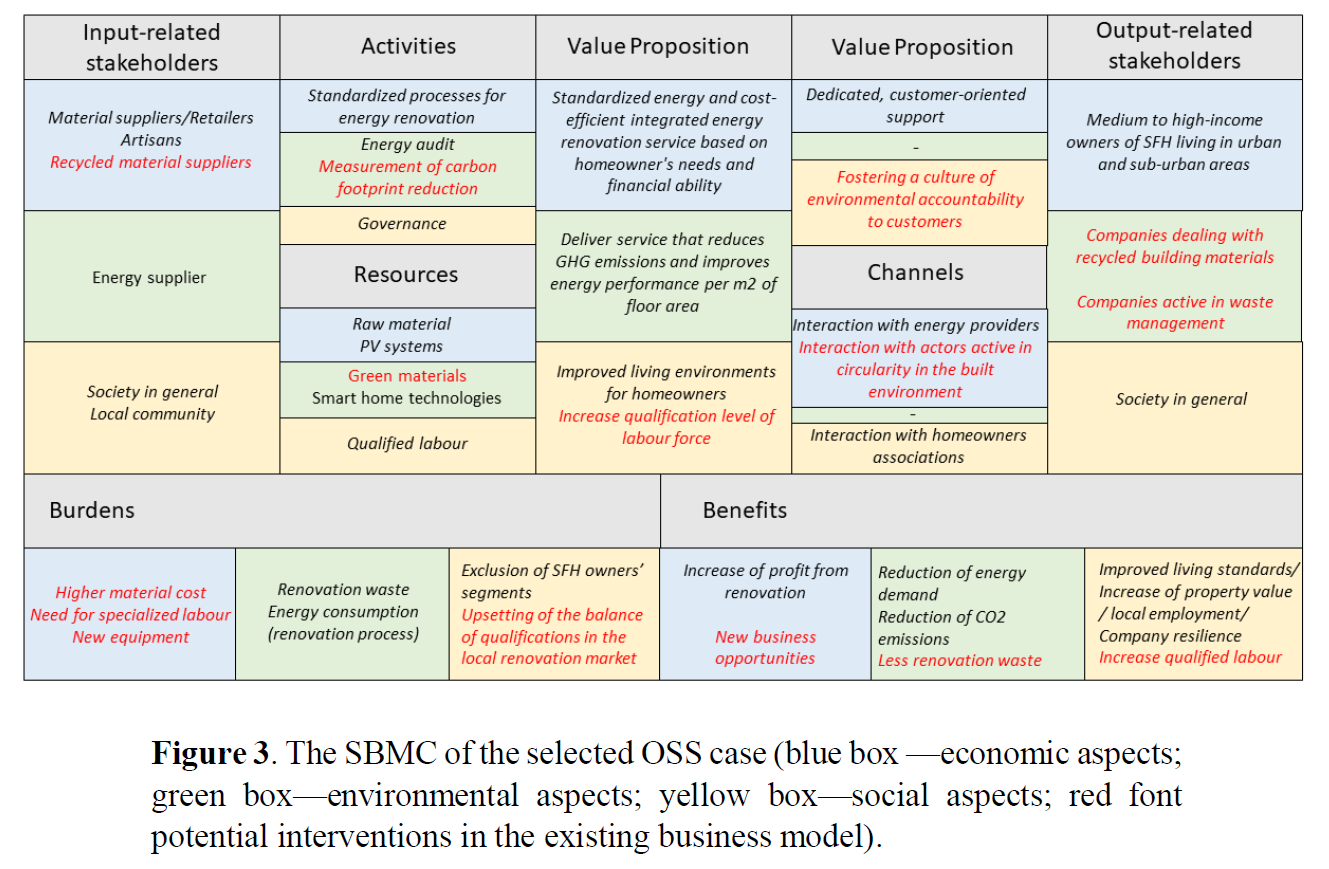

606. Pillars as a business model canvas (Pardalis 2022)

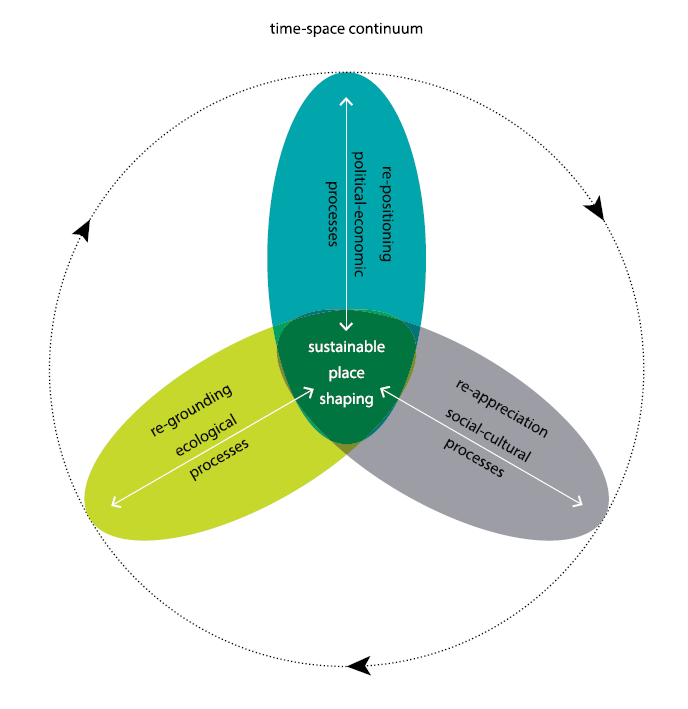

607. Sustainable place shaping (Horlings 2020 after Roep).

- Re-appreciation. People attach meanings and values to place and reflect on the relations which they are part of. Re-appreciation is the starting point of awareness of place identity, which can result in a ‘proud of place’ and a joint mobilization around new storylines and agendas for the future (Grenni et al. 2019).

- Re-grounding. A re-grounding of practices in place-specific assets and resources, can potentially make them more sustainable. Practices of sustainable place-shaping are influenced by wider communities, cultural notions, values, natural assets, technology and historical patterns, illustrating existing variations in institutional and cultural contexts.

- Re-positioning. The re-positioning towards the established institutions, or dominant regime such as government and public policies, business and markets and the innovation system evolves by creating experimental spaces or niches. Re-positioning includes a critical perspective on how our economic system is organized and what might be sustainable alternatives that shape places can enhance the quality of life in places.

608. Transformative social innovation (Mehmood 2020)

Sustainable re-learning, re-experiencing, and re-generation processes to reshape places in a transformative way.

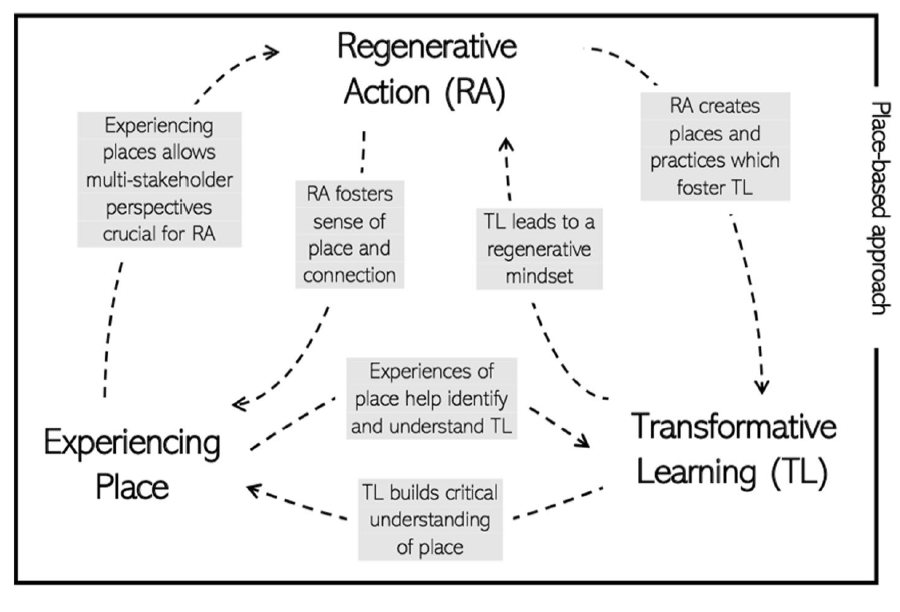

609. Regenerative decision making (Craft 2021)

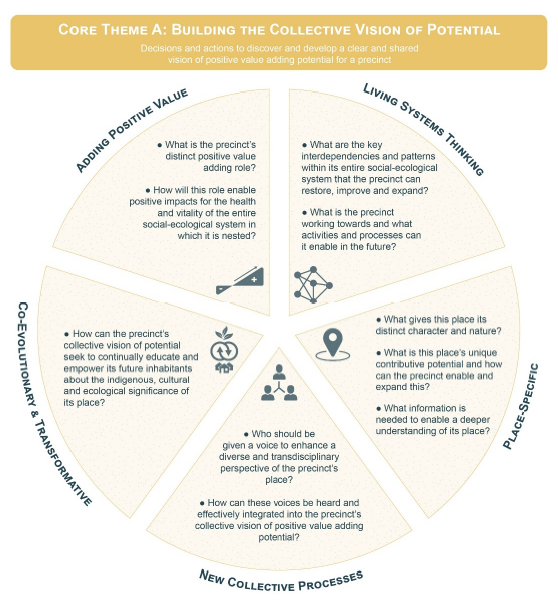

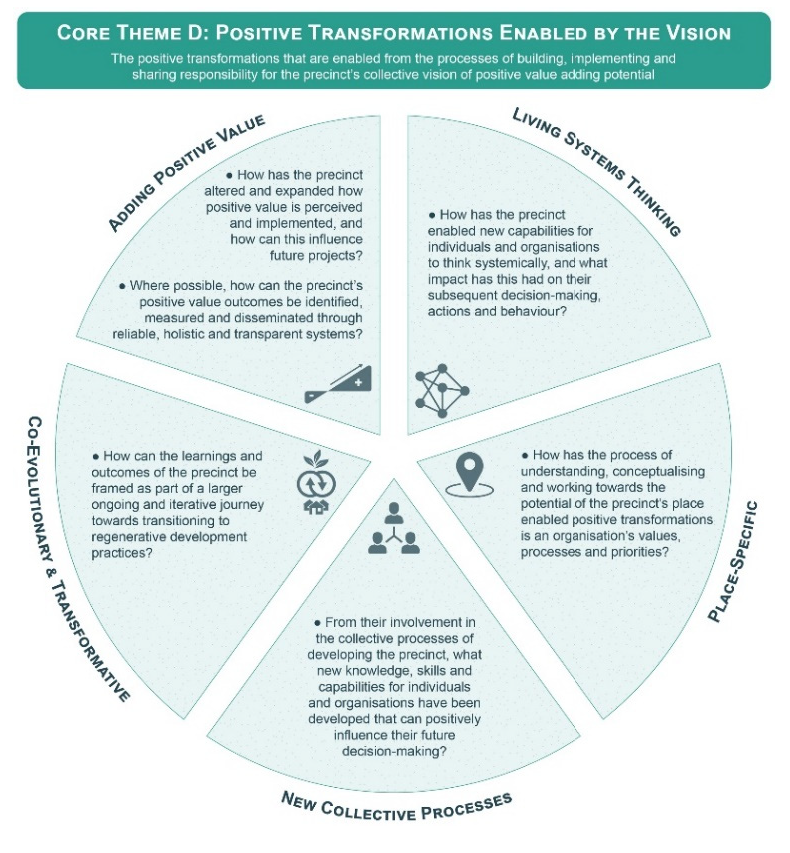

610. Collective vision of potential (Craft 2021)

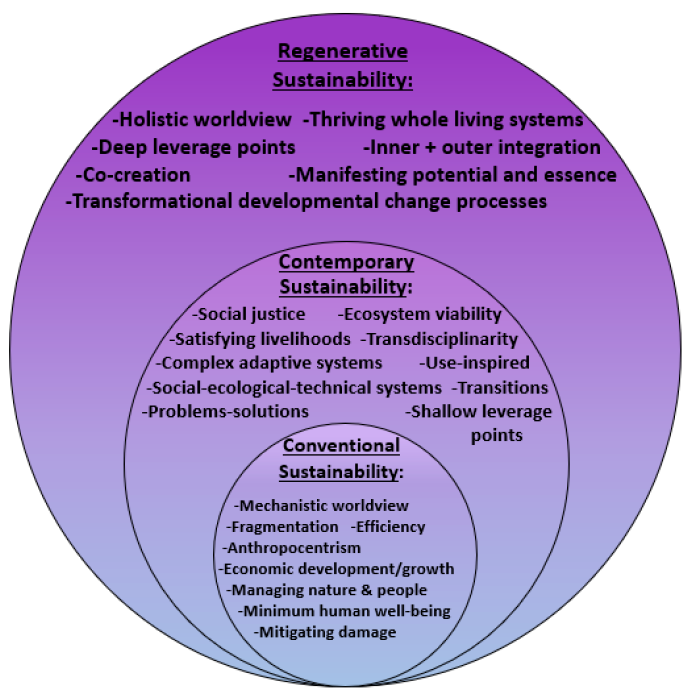

611. Sustainability Paradigms (Gibbons 2020)

Different sustainability paradigms have developed through time, each including and transcending the previous. Conventional and contemporary sustainability are based on a mechanistic worldview and are largely anthropocentrically focused. Contemporary sustainability advances conventional sustainability by including concepts such as justice, complex adaptive systems, and transdisciplinarity. Regenerative sustainability, the next wave of sustainability, is based on a holistic worldview and aims for thriving whole living systems. It integrates inner and outer realms of sustainability and focuses on shifting deep leverage points in systems for transformational change across scales.

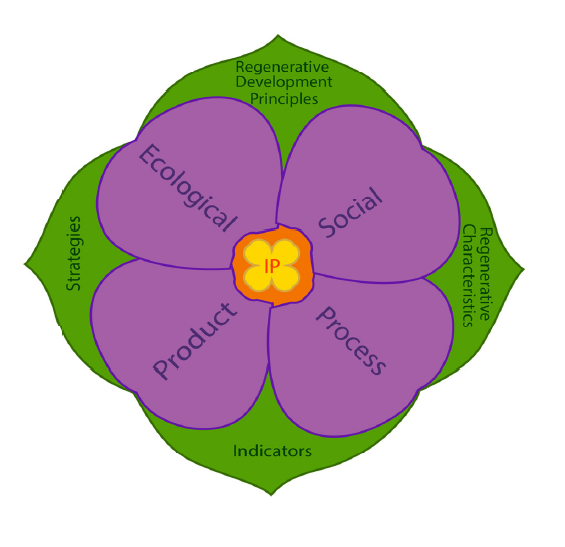

612. Flower (pretty and regenerative ) (Gibbons 2020)

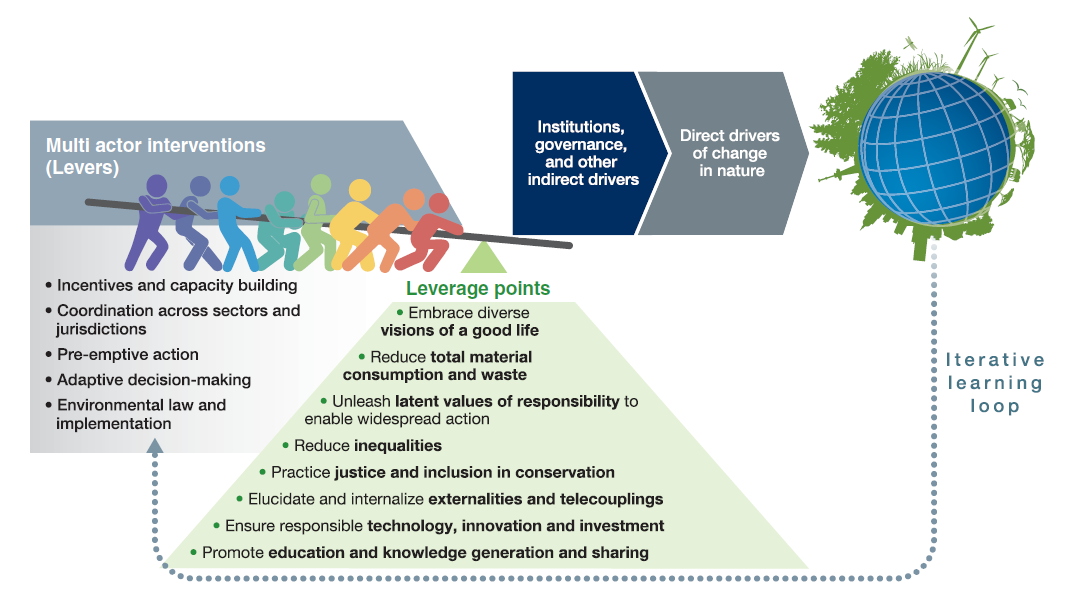

613. Meadows’ leverage points with multiple actors and learning (Chan et al. 2019)

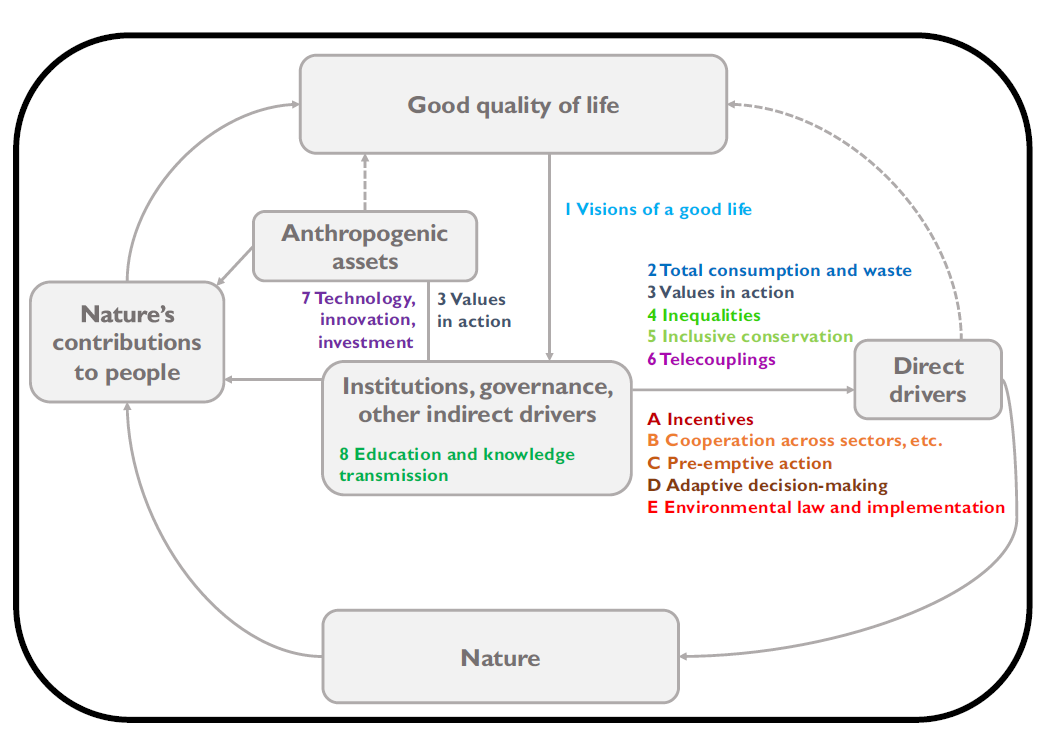

614.Leverage points and sites of action (Chan et al. 2019)

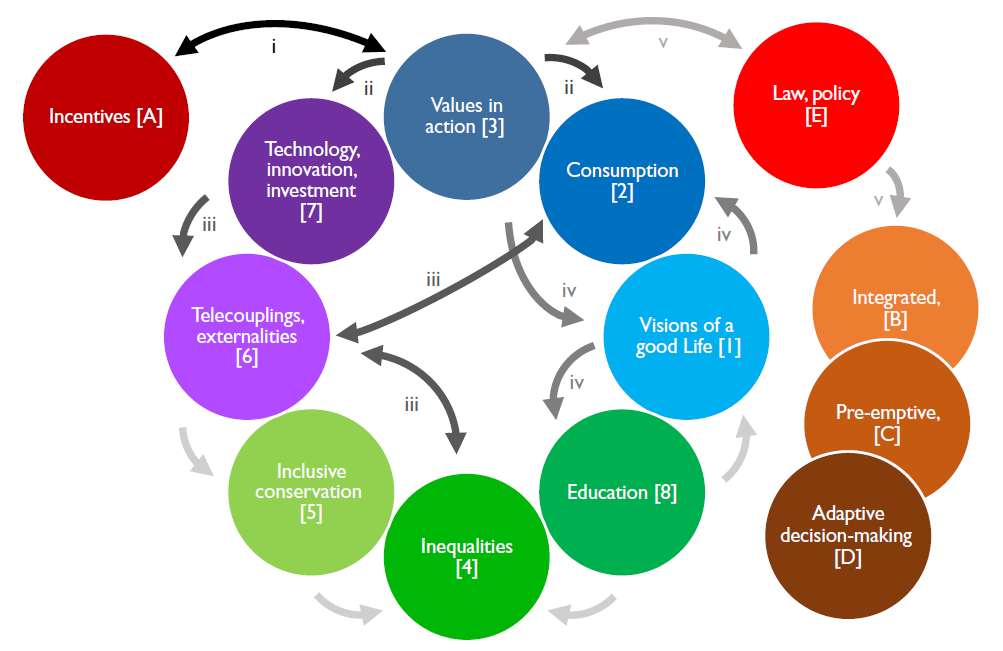

615. Causal Chain of Levers (Chan et al. 2019)

[1–8 refer to leverage points, and A–E refer to levers]. First, (i) a new incentive programme [A] provides a means for individuals and organizations to express their latent values of environmental responsibility [3] by paying for diverse resource users and land/water stewards to conserve and restore ecosystems, mitigating unintended negative environmental impacts associated with supply chains. These co-payments thus provide incentives that enable additional value-oriented action. (ii) Both the consumer/organizational action and the new conservation/restoration trigger [7] innovation in practice and appropriate technology. The consumer/organizational action of committing to pay for mitigation of their impacts might have the effect of [2] reducing consumption. (iii) Both the innovation and the reduction in consumption rein in [6] negative environmental externalities. Because many negative externalities have disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations, this could [4] reduce some inequalities. (iv) As a socially conspicuous way for people to enact latent values of responsibility, the practice becomes normal and helps shift (1) visions of a good life away from conspicuous consumption. This further [2] reduces consumption and enhances [8] education about social–ecological problems, systems and solutions. (v) The value-enabled action may then facilitate changes in [E] laws and policies, and their enforcement, with four effects: [3] consolidating value-based action; [B–D] shifting management and

governance systems to be integrated, pre-emptive and adaptive; further increasing [8] education and knowledge transmission about nature and sustainable resource use; [5] enhancing broad and appropriate inclusion of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in conservation and restoration; and [1] eliminating harmful production–enhancing subsidies/incentives (last two arrows not shown for simplicity). Unlabeled silver arrows depict a small subset of additional synergies by which one leverage point might facilitate others

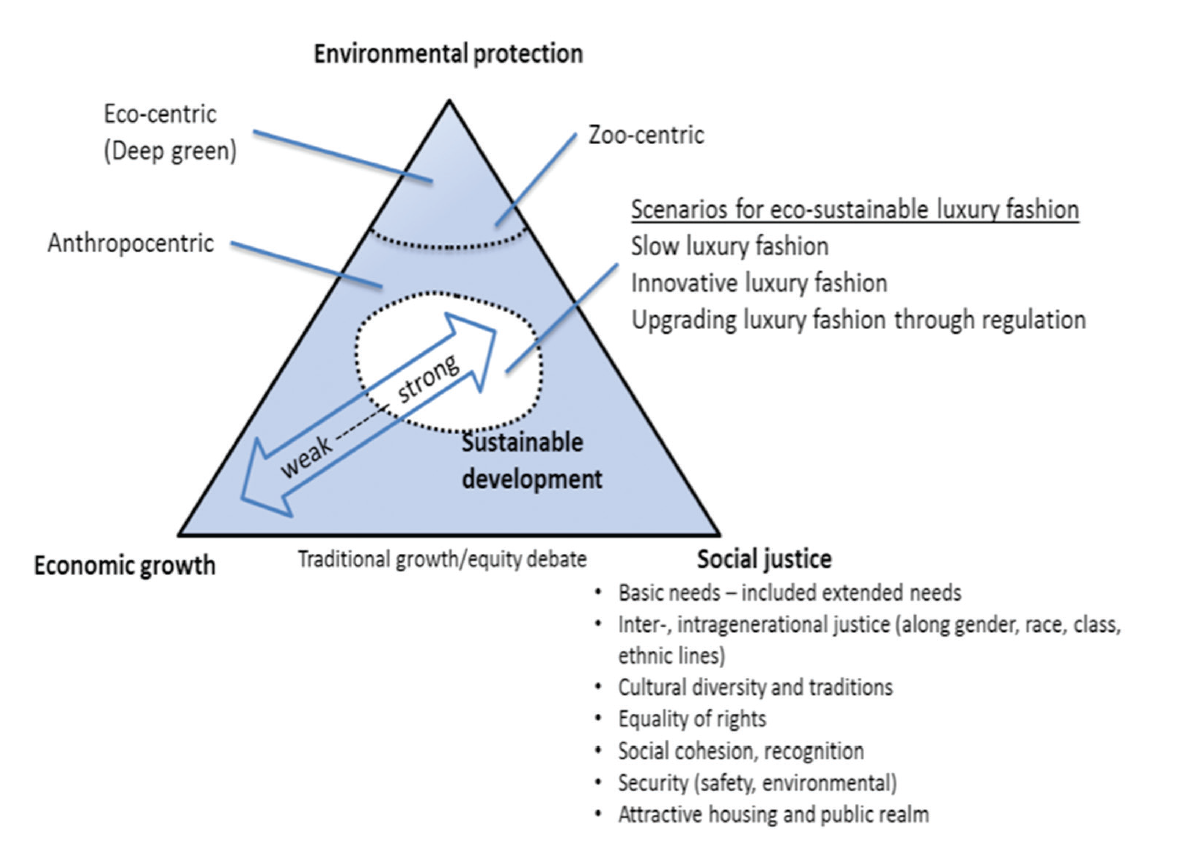

616. Pillars on a triangle – so as zero-sum competing forces. With weak-strong sustainability arrow and zone for luxury fashion (Csaba 2018)

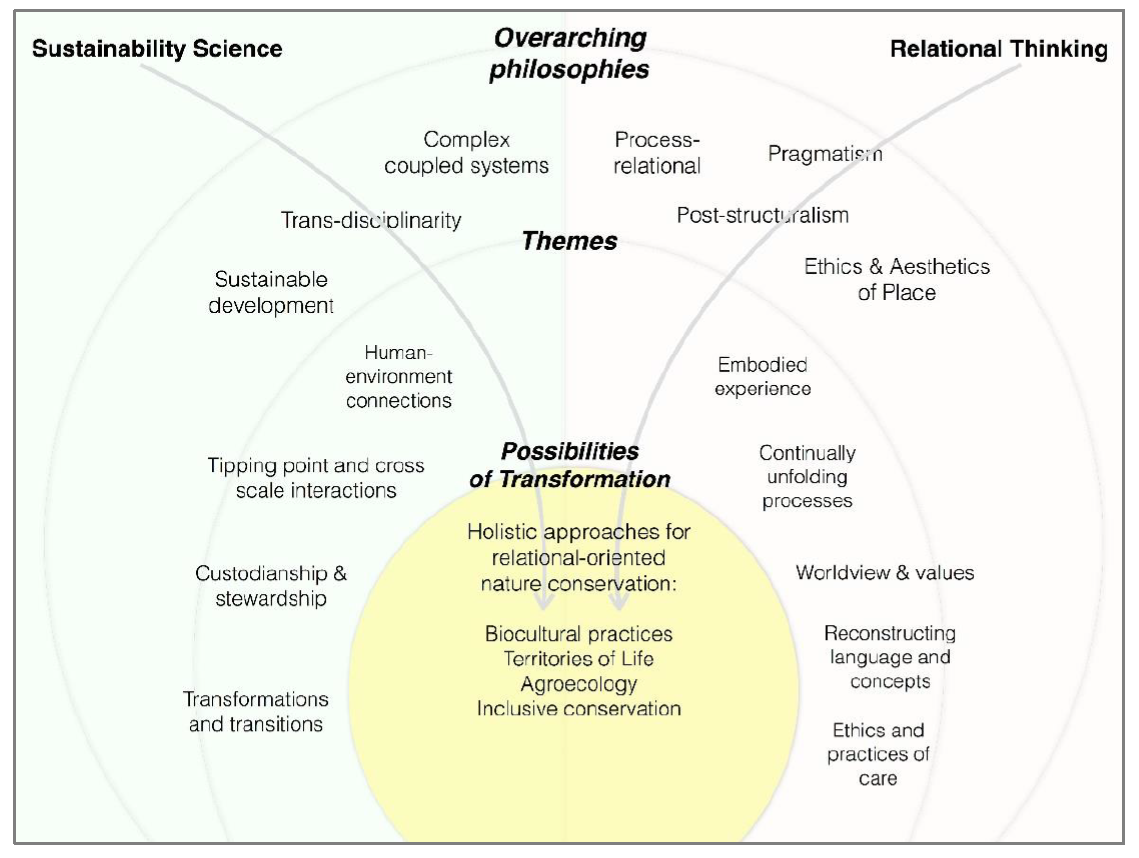

617. Relational approaches (Foggin – thinking like a mountain 2021)

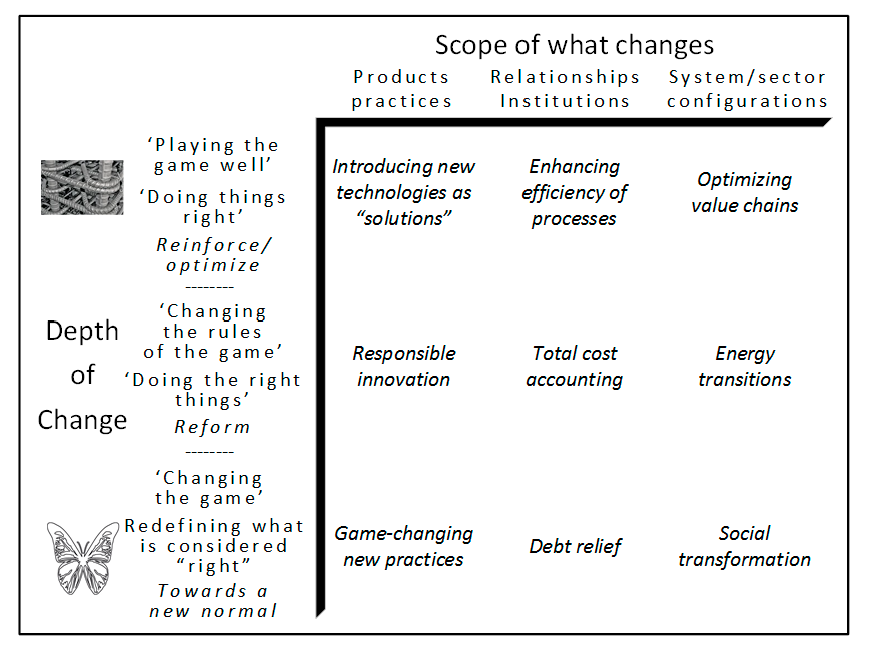

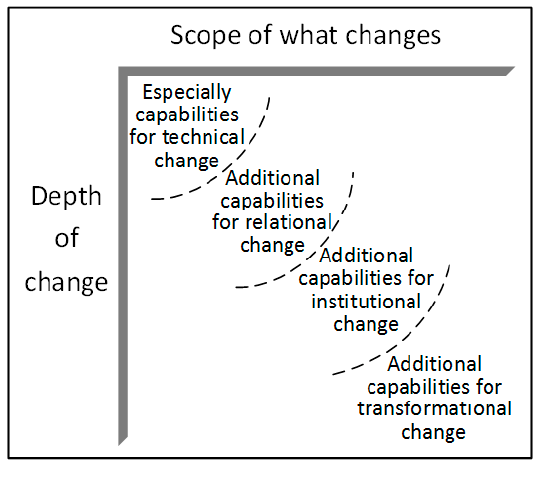

618. Scoping canvas (plus bonus capabilities and transformation) (Wigboldus 2020)

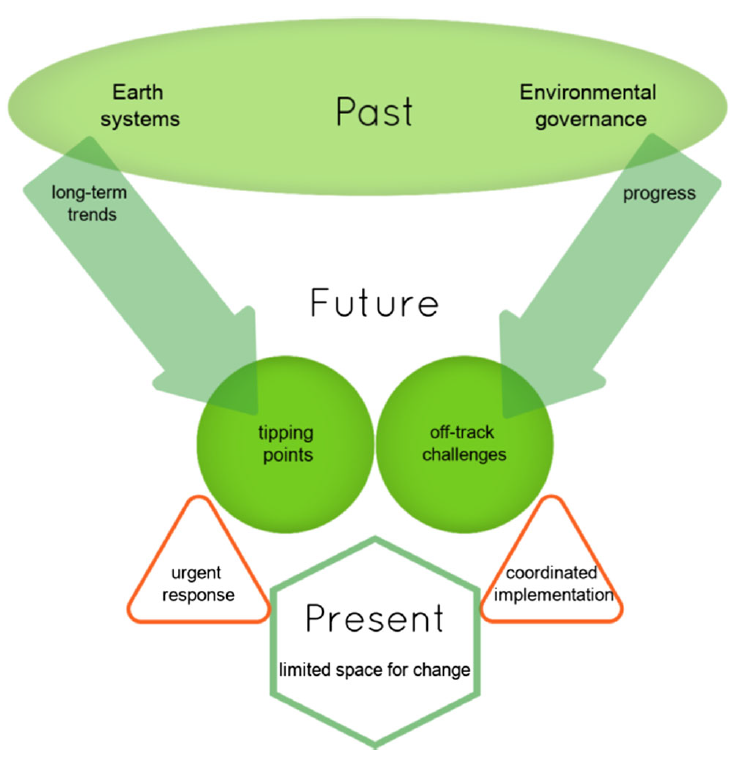

619. Sustainability as transformation but still framed by past (Priebe 2020, leading to Marald and Priebe‘s metamorphosis).

620. Connecting inner and outer leverage points (Woiwode 2021)

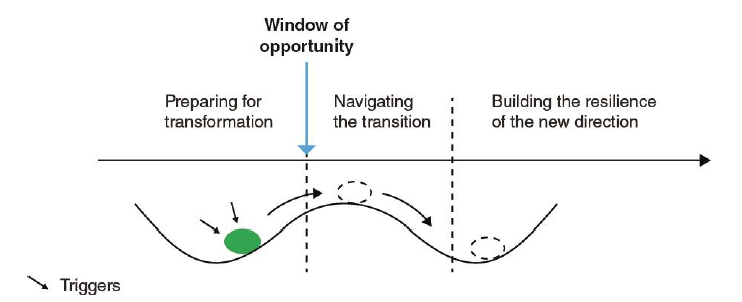

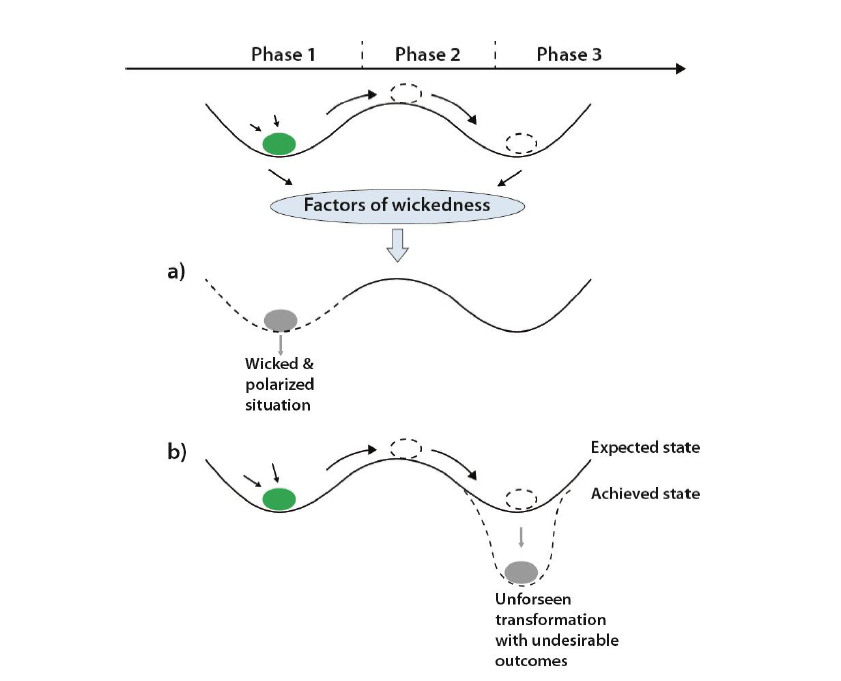

621. Socio-ecological transformation, but challenges of wickedness (Sediri 2022)

622. Marketing sustainability pyramid (Lim 2022)

The proposed model is not at odds with existing approaches to sustainability, but rather aims to provide a clearer focus on how to approach sustainability dimensions in a way that moves the larger society toward greater sustainability,

The core tenet of the sustainability pyramid is that sustainability dimensions at the bottom of the pyramid should be addressed first before addressing higher-level sustainability dimensions. The economic

dimension is at the bottom of the pyramid because the root of sustainability-related problems is unsustainable consumption, which is caused by consumers. For the large majority of consumers, economic value is the main consideration in their purchase and consumption of goods and services. Without being convinced of economic value, mainstream consumers are unlikely to consider the social and environmental value that sustainable products and practices entail.

623. Mindfulness and inquiry. (Wamsler 2016)

624. Nature Futures Framework (Duran et al 2023).

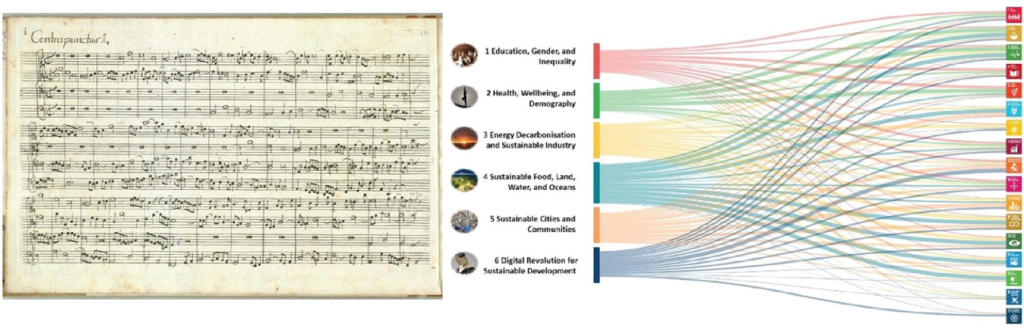

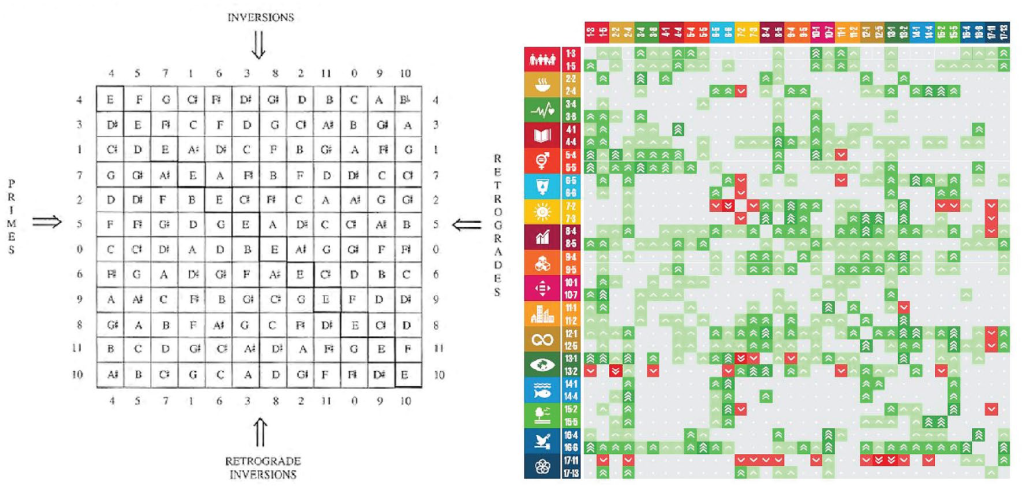

625. SDGs as music theory (Veland 2021)

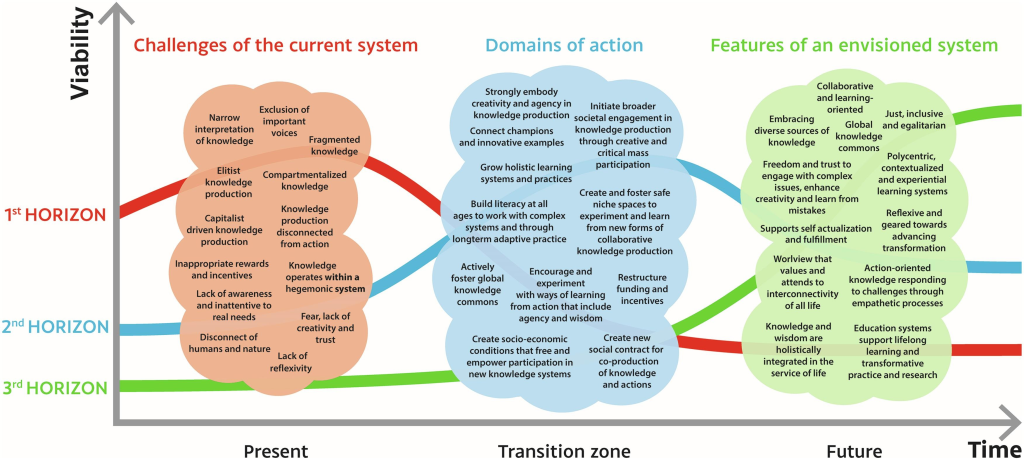

626. Three time horizons to regenerative and equitable future (Fazey et al 2020)

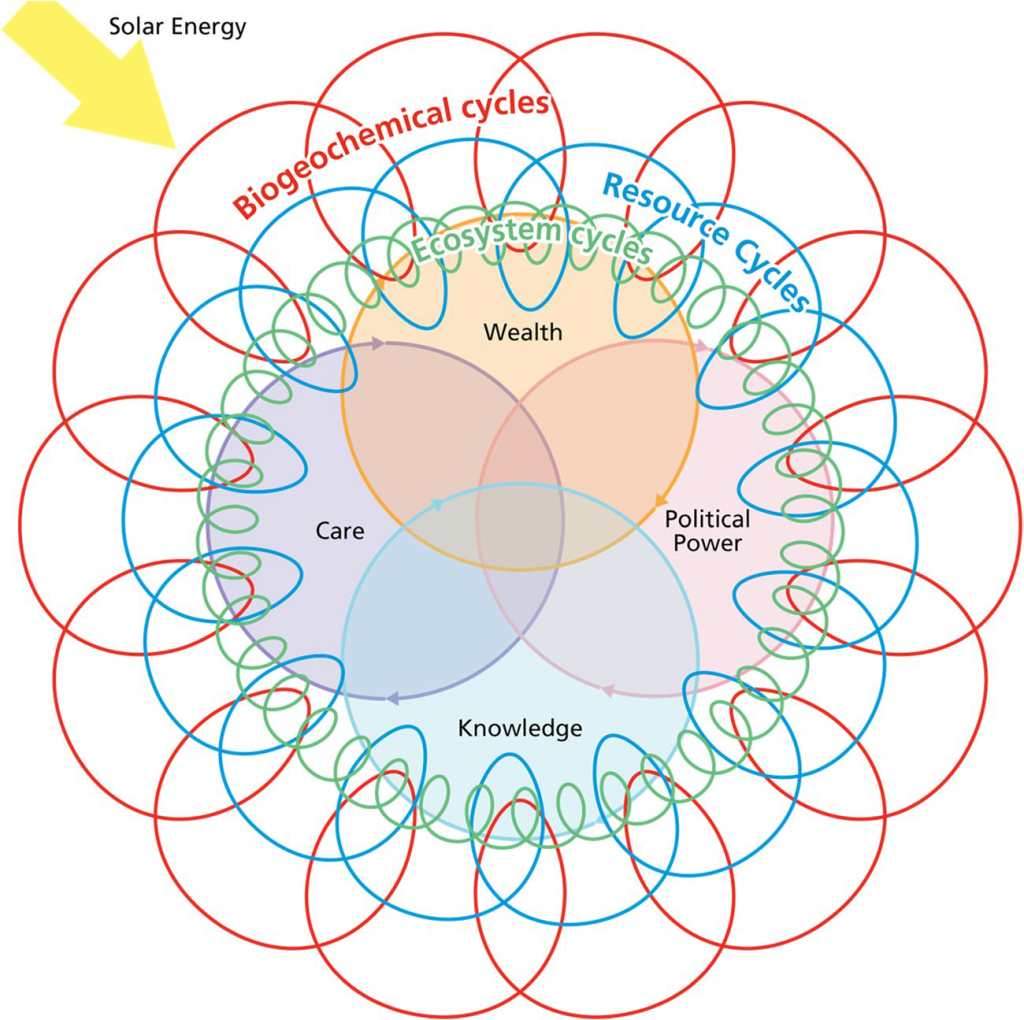

627. Seven interrelated cycles (Calisto Friant 2023)

OK, not really sustainability, but allows them to say:

Addressing a problem related to

“Any of the seven cycles thus necessitates a broad understanding of the interactions and interrelations between all cycles”

“All in all, the core value of representing these seven cycles resides in helping us understand what circularity” and “circular” flows can be about in relation to sustainability and human and planetary well-being. They help expand the imagination regarding what is and what isn’t included as a “loop”, “cycle”, circle”, or “flow” when we talk of a “circular” economy and society.”

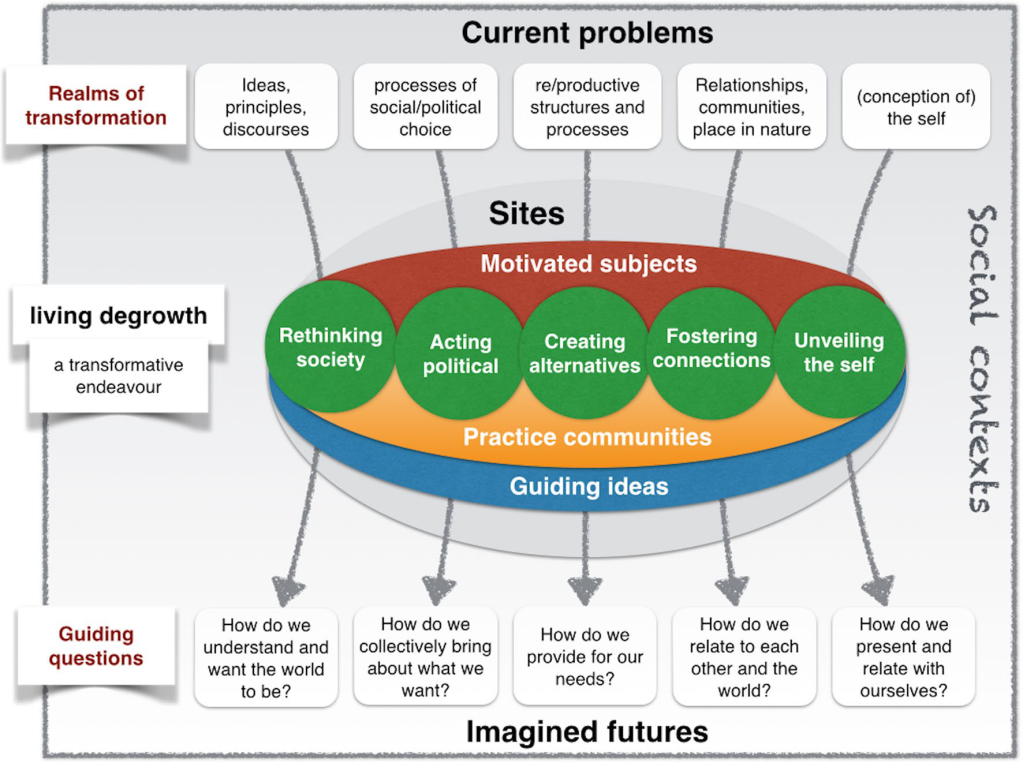

628. Performative degrowth (Brossmann 2019)

629. Virtuous Spiral (Turnbull 2021)

Sustainability spiral model; a conceptual diagram in which the people-policy sub-cycle empowers local stewardship and improves the effectiveness of institutional stewardship, which combine to drive ecological outcomes in the main social–ecological virtuous cycle. Ecological outcomes result in improved ecosystem services and values, which motivate further stewardship; b spiral model representing multiple iterations of the virtuous cycle over time, progressing towards sustainability goals

631. Life Framework of Values (O’Connor 2019)

ES ecosystem services, NCP nature’s contributions to people

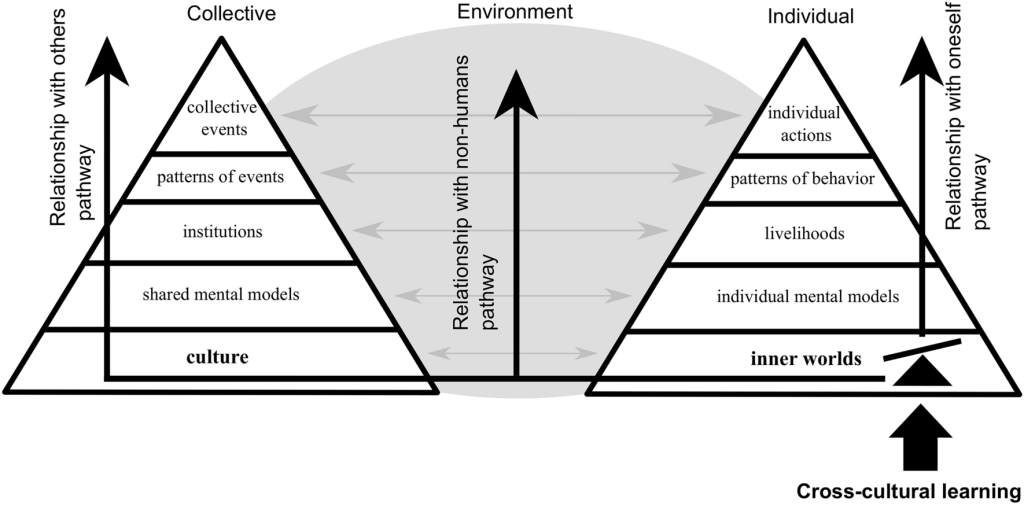

632. Inside-out pathways (Gray 2021)

Cross-cultural learning as an individual deep leverage point to activate three inside-out pathways towards sustainability transformations

(triangles are Nguyen and Bosch’s Five-level iceberg model including inner-worlds)

Theoretical model of cross-cultural learning as an individual deep leverage point to activate three inside-out pathways towards sustainability transformations

633. Expanding egg. Leverage points and biomimicry (Davelaar 2021)

634. Tanglegram of discourses. (Walsh 2021).

635. Sustainable Livelihoods Model (Natarajan 2022)

(has a non-overlapping pillars model at the core).

636. Still Sustainable Livelihoods Framework, now a web of relationships (Chaya 2022)

637. End-goal of environmental peace-building (Dresse 2019)

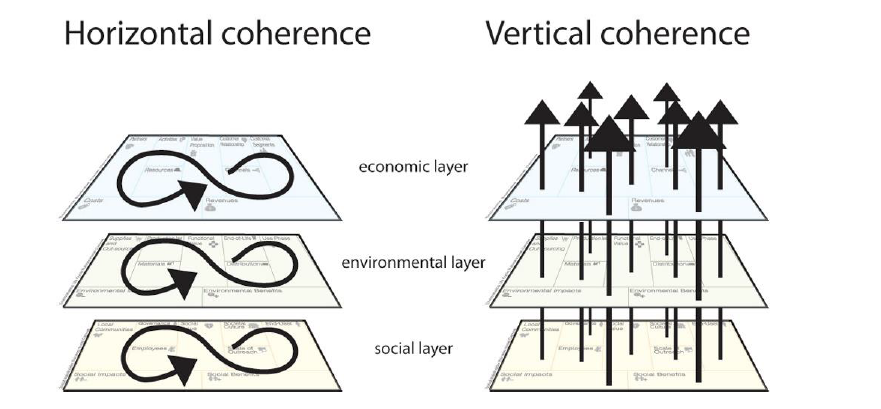

638. Sustainable Business Model (Lozano 2018)

At its core is a two-pillar model – with no mention of society.

639. Regenerative mindset framework – more than human ethic of care (Seymour 2023)

640. Images of Nature (Heeren-Hauser 2020)

641. Invisible (bio)economies: a framework to assess the ‘blind spots’ of dominant bioeconomy models (Pungas 2023 adapted from the Bielefeld Subsistence approach and Coloniality–

Capitalism–Patriarchy Nexus Mies et al. 1988)

642. Snakes on a plane. (de Vries 2021)

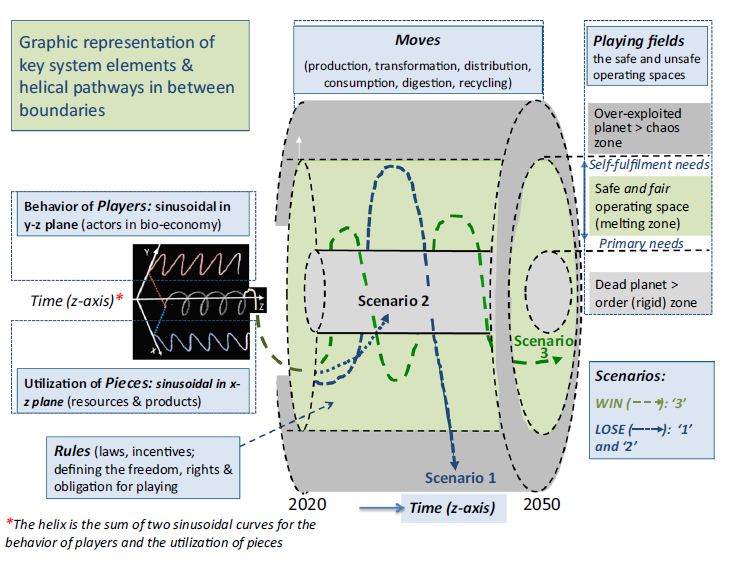

Which ‘confinement’ area allows systems to follow sinusoidal-like patterns? We start with the integration of the time dimension in the previously presented ‘doughnut’ and ‘radar’. This yields a novel cylinder configuration with three zones (Fig. 1), the order, melting, and chaos zones. The melting zone is a hollow cylindrical tube centered around a ‘highly ordered (rigid) zone’. This inner cylinder represents e.g.

the non-vital planet earth that is not able to respond to primary needs. A third, outer, cylinder represents a ‘highly chaotic zone’, e.g. the over-exploited or over-heated planet earth where excessive behavior leads to extreme and irreversible inequalities. Consequently, the melting zone can also be called a safe operating space in socialecological systems (Anderies et al., 2019; Rockström et al., 2009) or fair and safe

operating space (this publication); the latter refers to the reflections on framings of food as a commodity, commons, and human right (SAPEA, 2020). The cylinder configuration allows defining contrasting outcomes – presented as 3 different scenarios – for bioeconomy systems (‘win-lose’ in game theory; like SDG outcomes).

Besides, the other 6 key elements of systems or game theory (Neumann & Morgenstern, 1944) are presented, namely players, pieces, rules, moves, playing fields, and duration/time (the light blue text boxes). The element ‘players’ include all actors in bioeconomy systems (like producers, NGOs, public institutions, citizens); their overall behavior should follow pathways in the green area to reach a sustainable output.

643. Transition toward societal sufficiency (Troger 2021)

644. Narrative metaphors in business reporting (O’Dochartaigh 2019)

645. Learning for Sustainability Competency Tree (Margarita 2020)

Why a tree?

646. Sustainable well-being society (Hellström for SITRA 2015)

647. Dominant vs Life Affirming Metaphors (Glasser 2019)

648. Interconnectedness (Lehtonen 2019)

(the straight lines previously described as “problematic dichotomies of modern thinking”)

649. Four Schools of Common Tragedy (Cashore 2023)

Attempting to tighten what they see as loose use of tragedy of commons framing in political science.

650. Prism (Asyraf 2022)

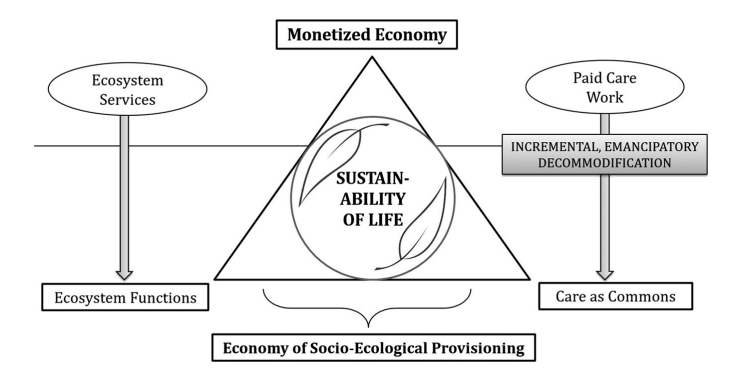

651. Incremental, emancipatory, decommodifying care for feminist degrowth (Dengler 2022)

652. Standardised! (Majerník 2022)

653. Plastic fantastic (D’Amato 2020)

Representation of key characteristics of a sustainability narrative: high degree of conceptual plasticity, quintessential core of archetypical solutions, contextually-tailored implementation

654. Values in transformational sustainability science (Horcea‑Milcu 2019)

OK, strictly it is about a model of sustainability science rather than sustainability itself. But how unnecessarily cute is that?

Posted on June 26, 2023

0