And I foolishly thought I would be able to stop at 500.

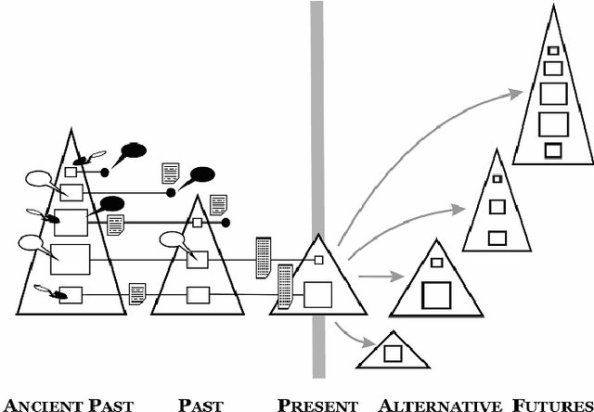

501. Back to the future (Pitcher 2005)

Diagram illustrating the ‘Back-to-the-Future’ concept covering the restoration of past ecosystems. Triangles at left represent a series of ecosystem models, constructed at appropriate past times, where vertex angle is inversely related and height directly related to biodiversity and internal connectance. Time lines of some representative species in the models are indicated, where size of the boxes represent relative abundance and solid circles represent local extinctions. Sources of information for constructing and tuning the ecosystem models are illustrated by symbols for historical documents (paper sheet symbol), data archives (tall data table symbol), archaeological data (trowel), the traditional environmental knowledge of indigenous Peoples (open balloons) and local environmental knowledge (solid balloons). Alternative future ecosystems, restored ‘Lost Valleys’, taken as alternative policy goals, are drawn to the right.

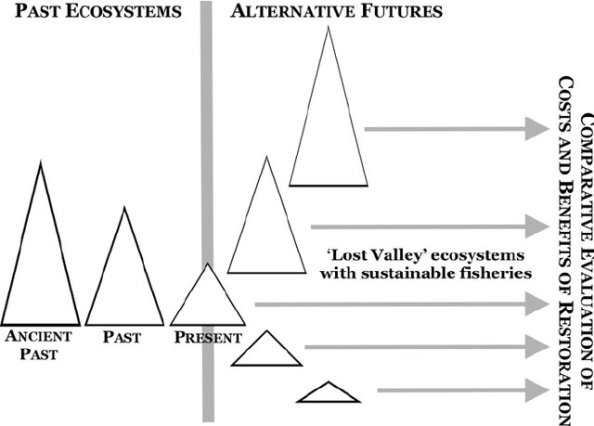

502. Environmentally oriented anti-consumption (EOA García-de-Frutos 2018)

Each pentagon can be subdivided into squares and triangles: above the curved line, squares denote areas of concern approached from an anti-consumption perspective;

under the curved line, triangles represent areas of concern approached from a consumption perspective.A more strict delimitation of EOA includes only those behaviors that imply the reduction, avoidance, or rejection of consumption for environmental considerations (depicted by the green box located in the upper part of the environmental area of concern in Fig. 1).

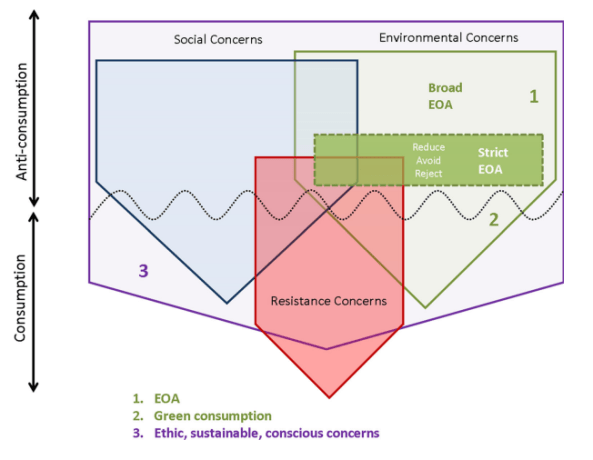

503. Sustainability (narrowly defined as efficiency) and resilience (Elmqvist et al. 2019)

The relationship between sustainability (narrowly defined as increased efficiency) and general resilience. a–c, The main drivers/outcomes of different combinations of resilience and sustainability thinking. Examples from the energy sector could be: large-scale carbon-capture technology (a), individual distributed solar technology connected in large regional grids (b) and no-grid individual household renewable energy sources (c).

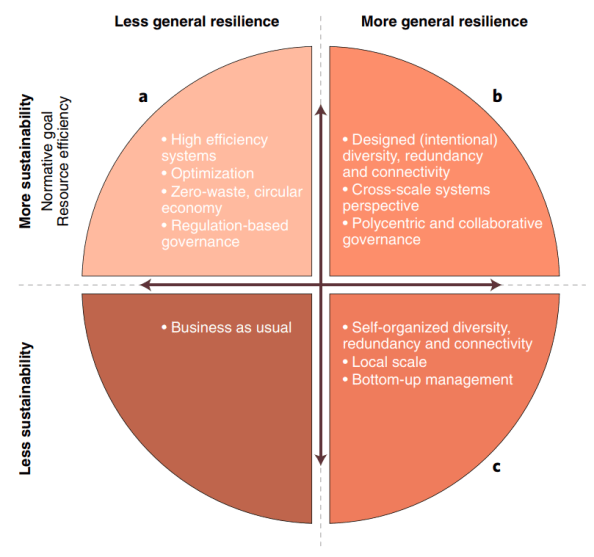

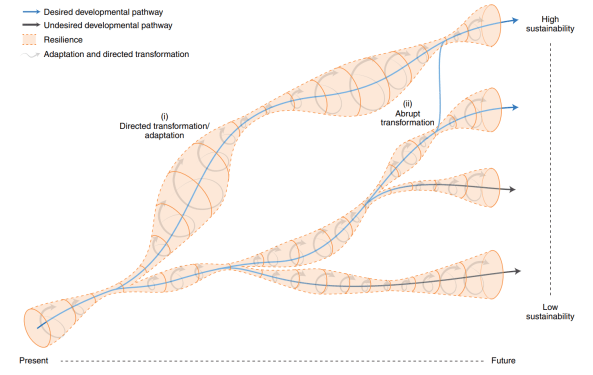

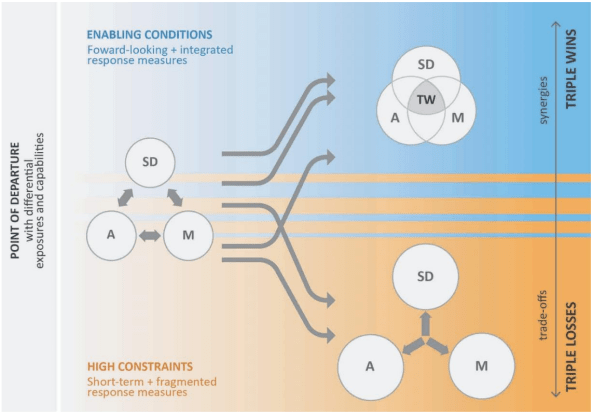

504. Interlinkages between sustainability, resilience and transformations (Elmqvist et al. 2019)

The notion of ‘directed transformations’ ((i) in Fig. 2) represents proactive actions that are dependent on some degree of system resilience to buffer effects of external disturbances, experimentation, mistakes and errors, that is, capacity to deal with uncertainties. It could also be represented by urban challenges where strong path-dependencies and investments in infrastructure to fulfl one function have created a lock-in situation lasting decades to centuries. Transformations in such cases represent how inventions of new functions of existing infrastructure are made and implemented to meet new demands (compare with urban tinkering approaches). Transformations typically involve changes in features like power relations, resource flows, meaning and values, roles and routines—and the interactions between them. A key to achieving sustainability is that these transformations also involve a fundamental shift in human environmental interactions and feedbacks. Such transformations include not only changes in landscape but also changes in the use and function of abandoned infrastructures, creating new urban economies and new urban flows of people and services.

‘Abrupt transformation’ ((ii) in Fig. 2) is much more fundamental and involves maintaining a function (for example, transport and mobility) but shifting structures (for example, from a ground street-based transport system to a cable-car or

air-based system). These more fundamental changes are often influenced by and could themselves influence drivers and connections at local, regional and global scales. Social innovation is demonstrated to play an important role in abrupt

transformations by showing alternative uses and configurations or reconfigurations of structures for maintaining a function or service in a system.

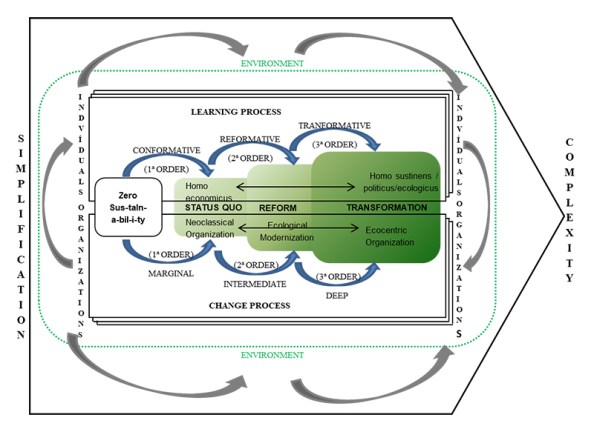

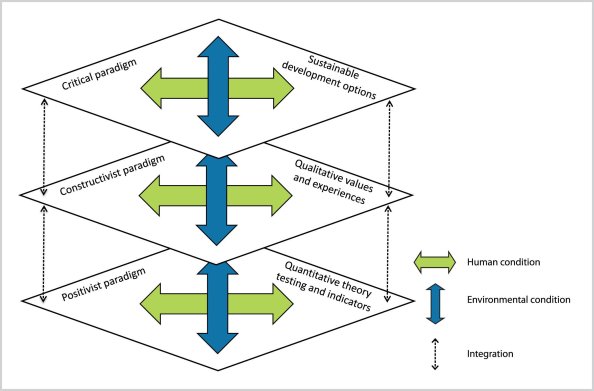

505. Transformative Sustainability Learning Framework (Palma 2014, via Palma 2019)

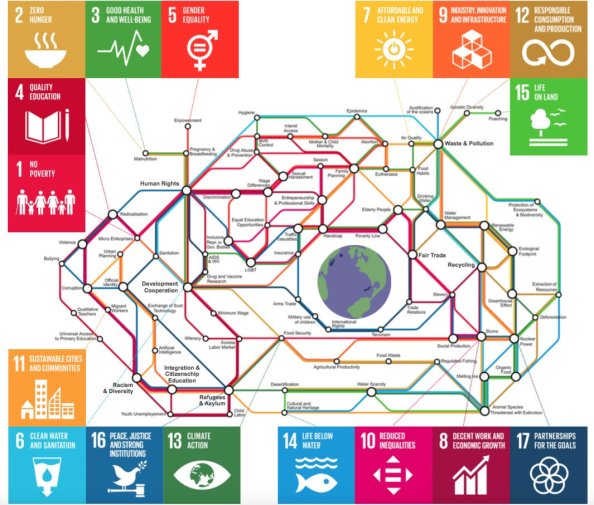

506. Underground map (via @TheUNTimes @zelfstudie)

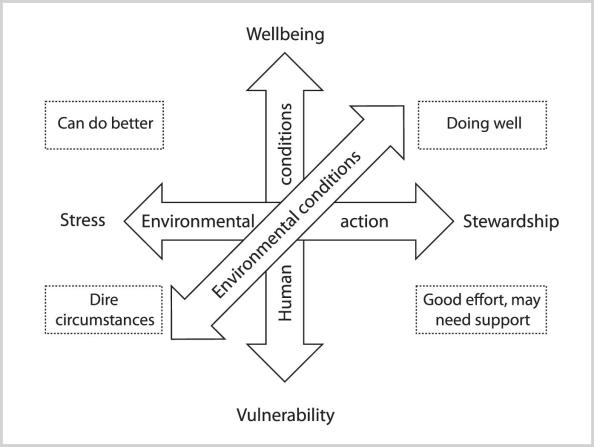

507. Human dimensions (of mountain development) (Flint 2016)

508. Integrated paradigms (Flint 2016)

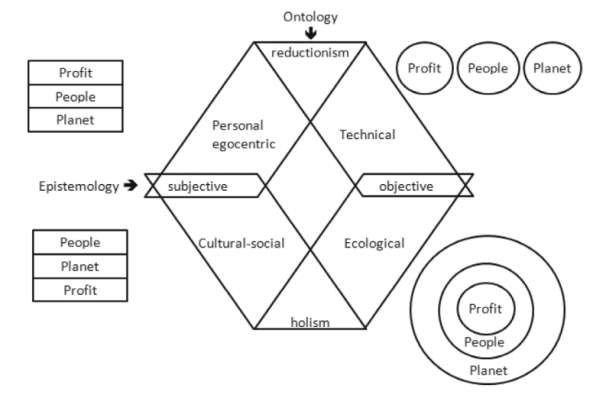

509. Different worldviews result in different P ranking (Boonen 2012)

One way to analyze different worldviews is by dividing them by focusing either on their ontological status (reductionism versus holism) or on the epistemological status (subjective versus objective). Combining these two gives us four different worldviews: personal-egocentric (subjective-reductionist), culturalsocial (subjective-holistic), ecological (objective-holistic) and technical (objective-reductionist). For each of those four worldviews, a 3P-ranking can be made.

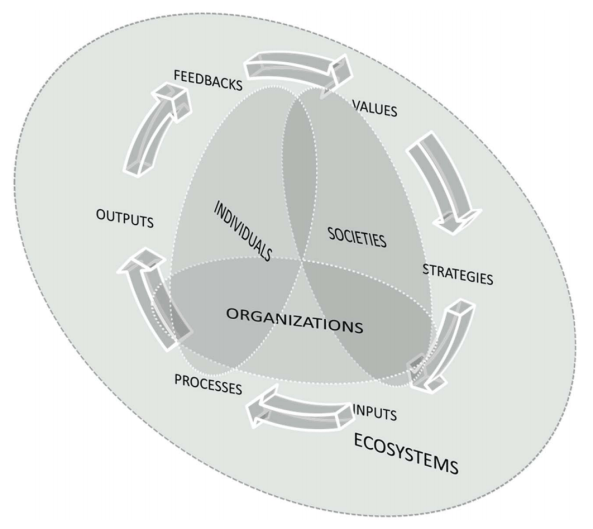

510. Multi-level, multi-system of sustainability management (Starik and Kanashiro 2013)

Uncovering and Integrating the Nearly Obvious

A multi-level, multi-system perspective of a proto-theory of sustainability management. Note. Systems of individuals, organizations, and societies are comprised of and are embedded in ecosystems. Such systems include humans and nonhumans (i.e., plants, animals, microbial organisms, and all forms of life). Feedback loops between and within systems have a focus on human long-term social, economic, and environmental needs. Policies prescribe integrated solutions to urgently address environmental and socioeconomic challenges.

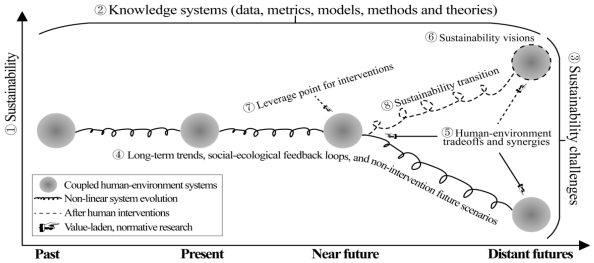

511. Eight-theme framework of sustainability science (Fang 2018)

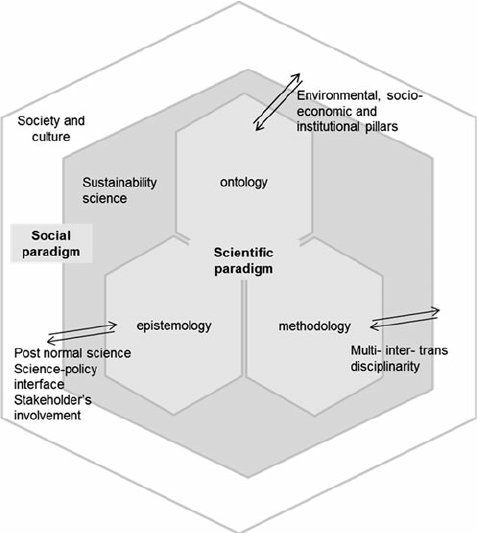

512. Interface between paradigms (Sala 2013)

Conceptual framework for sustainability science as interface between scientific and social paradigm for handling sustainable development challenges characterised by complex relationship between nature and humankind are. The scheme has to be considered on a multi temporal and spatial scales.

513. Rocket Catalyst (Global Nutrient Report 2017)

(Small numbers SDGS, large numbers part of a larger infographic)

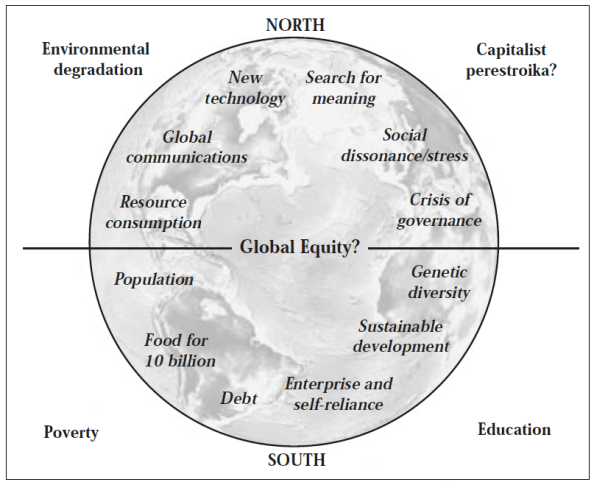

514. The world problematique – the scope of unsustainability (Tibbs 1999)

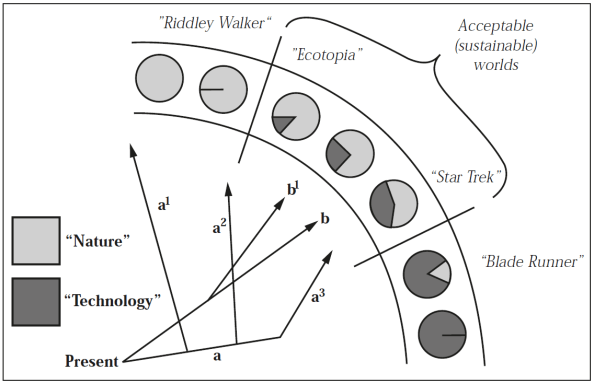

515. Pathways to sustainable future worlds (Tibbs 1999)

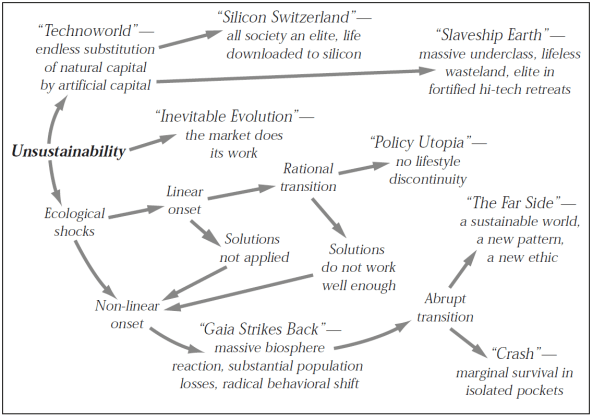

516. Scenario family tree: the outcomes of unsustainability (Tibbs 1999)

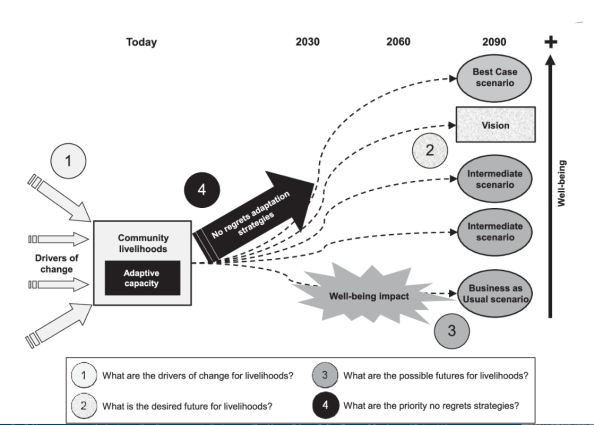

517. No regerts (Butler 2016)

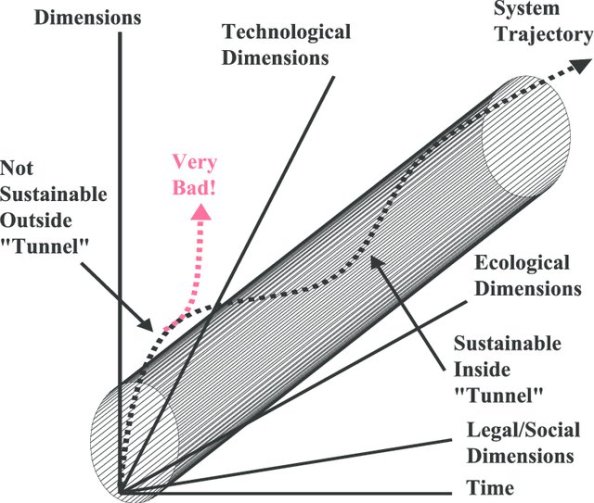

518. Escaping the tunnel is Very Bad! (Glaser 2004)

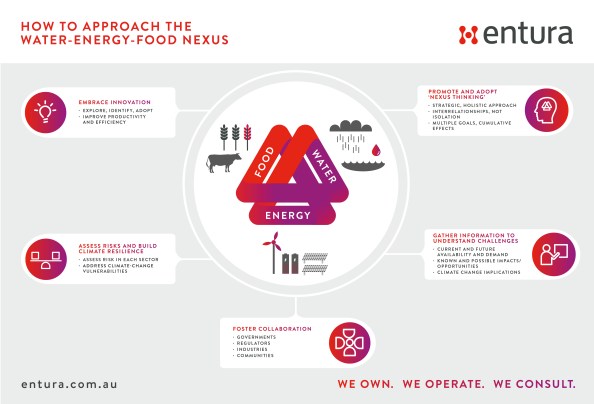

519. Nexus thinking (Entura)

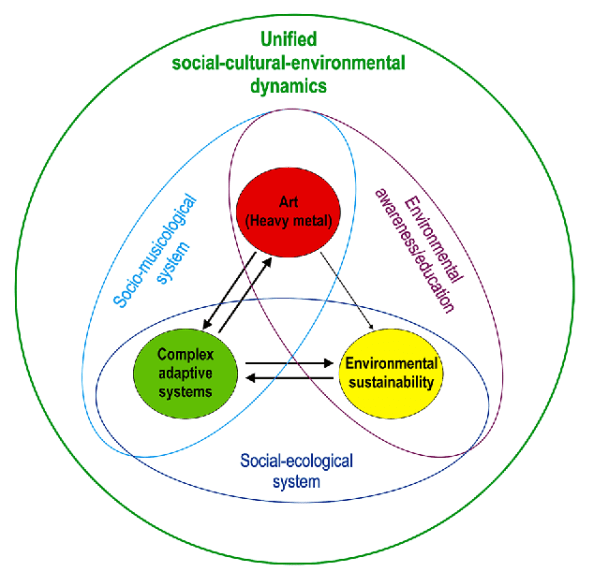

520. Heavy metal (Angeler 2016)

Schematic showing links between distinct, apparently unrelated knowledge domains. Shown are: (1) The links between heavy metal music and complex adaptive systems theory to describe the emergence of a socio-musicological system (light blue ellipse). (2) The potential of heavy metal music as an educational tool to increase awareness of environmental sustainability challenges (purple ellipse). (3) The links between complex adaptive systems and environmental sustainability that mediate social-ecological system dynamics (dark blue ellipse). (4) An emerging broader, unified picture of social-cultural-environmental dynamics (green circle). Arrow directions and thickness represent reciprocal versus unidirectional information potential between domains and interpretational objectivity versus subjectivity, respectively (see “Background” section)

521. Dynamics of system (Schwaninger 2015)

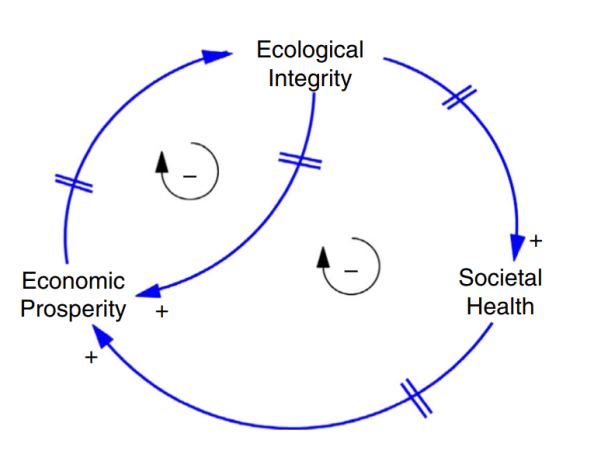

Ecological integrity furthers the health of a social system, which then enhances

economic prosperity. A thriving economy – as the evidence shows – can become

disruptive to the environment (therefore the negative sign on the arrow). That is what we have had in the industrialized world at least since Second World War, and

increasingly also in the emerging economies. The dynamics of this system are

summarized in the negative signum denoting a balancing loop: this appears to be a

self-regulating system, in which damages are eventually compensated.

Yet, the situation is more complex: a healthy environment enhances economic

prosperity. Accordingly, injuries to the environment result in dysfunctionalities of the economy. This makes another self-regulating loop, which is supposed to be a good omen. But the appearance deceives: there are delays in the system (marked by the crossbars in Figure 1). Due to these retardations it is likely that the economy thrives even more, until at some point the environment strikes back, unexpectedly and forcefully.

522. Recognition primary in justice related norms (Dawson et al. 2018)

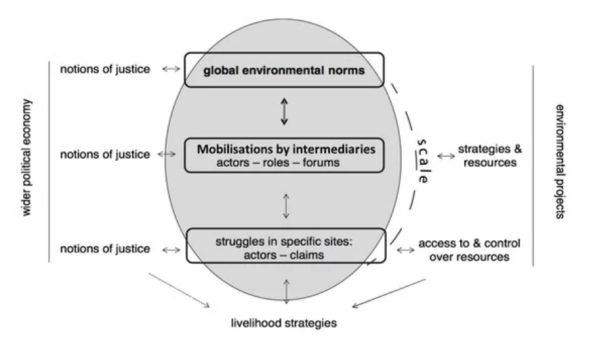

A common source of contention for local communities regarding environmental management, particularly cultural minorities and Indigenous Peoples, is lack of recognition of their worldviews, identities, values, place attachments and practices in policy design and decision-making processes

As a well-functioning, inclusive and just policy process, global climate and forest governance would incorporate the diverse justice-related norms of remote local communities and any marginalised or vulnerable groups among them [33,34]. Justice-related norms represent shared understandings or commonly-held standards of how things should be and how things should be done [26]. Those norms can be diverse, complex and dynamic and are not simply diffused upwards or downwards between policymakers and local communities. Rather, for the justice-related norms to effectively travel from local level to national or even international levels, they must be acknowledged, mobilised and (re)presented in dynamic policy debates [29]. This brings to the fore the role of intermediaries (or justice brokers), comprising state, private sector and civil society actors and institutions who operate across levels to mobilise local struggles for justice and to represent local issues and perspectives in different forums, comprising both formal and informal interactions and decision-making negotiations at various levels to ensure local norms effectively inform policies

523. Spheres of life (Mella 2015)

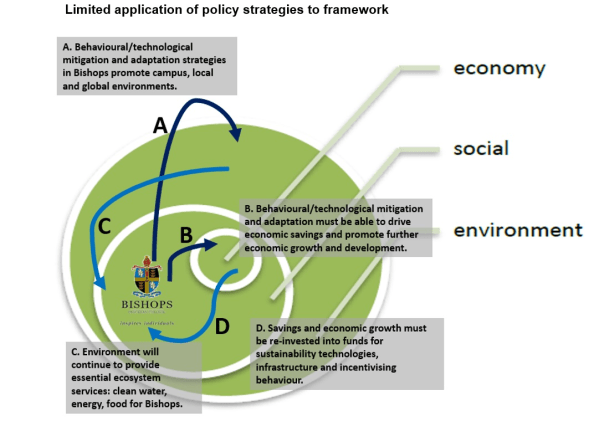

524. “Neo-sustainability” (ie strong) with relationships (Bishops College)

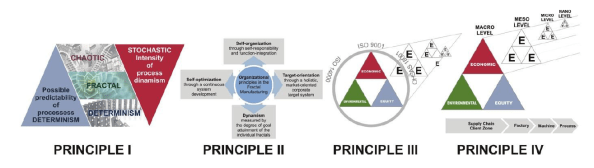

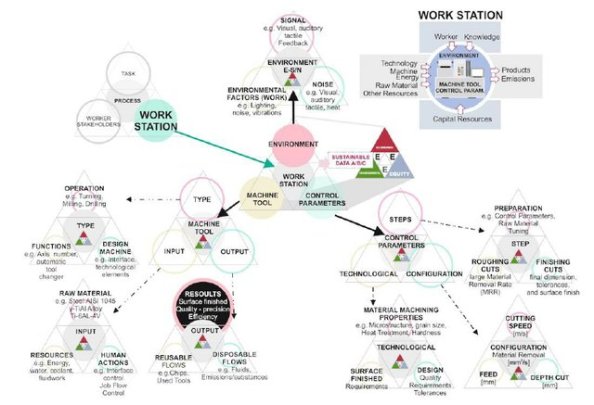

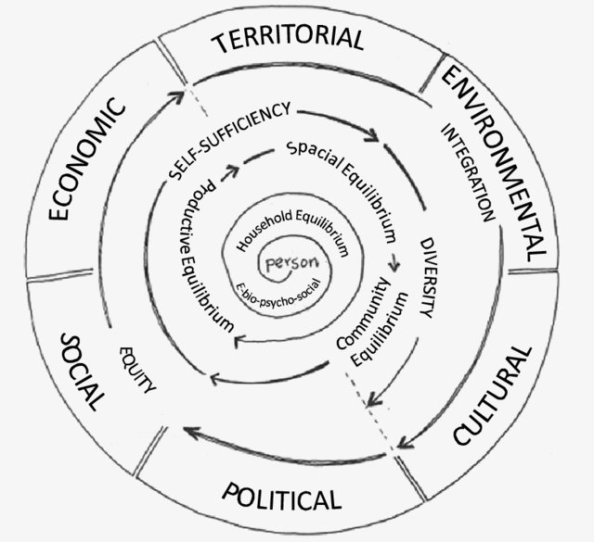

525. Self-organising fractal sustainability (Peralta 2015)

I. Principle of manufacturing organization fractal:

II. Principle of organization derived from the variety or fractalicity required:

III. Principle of fractalization of sustainable product’s life cycle: This principle develops the co-evolution between the fractal organization and the environment or ecosystem, to achieve a sustainable behaviour in the machining process. It proposes the integration of the social, economic and environmental perspective in the fractals of manufacturing in whole life cycle from the perspective of the variety required (minimum complexity). This

principle will enable the goal orientation of the fractal system: in this case, the objective is the sustainability. An organization that controls a Fractal Manufacturing Process with sustainable approach will be oriented to the sustainable results.

IV. Principle of fractal levels of sustainable manufacturing: This principle sets the level of fractalicity. All fractal of manufacturing will be structured in different fractal levels with the goal of moving and to achieve sustainable development in a similar way, like a natural fractal object does.

Processes at a micro-level

526. SDG pentagonal rotunda (Anthony Judge)

(See also discussion on representing oppositional drives)

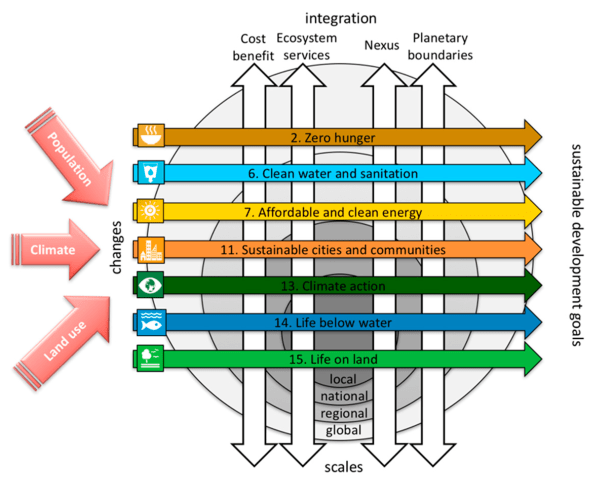

527. SDGs with scales and policies (Lehmann et al. 2017)

Selected SDGs (Annex 1) at various scales and under numerous global changes, with some existing integrative approaches to address them (Annex 2).

In order to avoid redundancy and dissonance, the new SDG framework should be linked to existing environmental policies. For instance, SDGs 14 and 15, which are about promoting the sustainable use of water and land ecosystems and halt biodiversity loss, should be in-line with the Aichi targets for 2020 defined by the Convention on Biological Diversity [3].

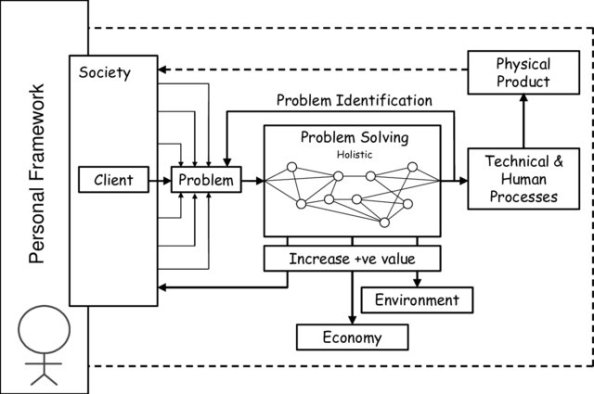

528. Way of life (L. Mann et al. 2007)

Category 5-Sustainable Design is a Way of Life (+ve is used to denote posotive)

529. Changing focus (in hydrology) (Zalewski 2015)

Evolution of the human approach towards the use of natural resources, starting from the belief of unlimited potential of nature to the recent awareness of the necessity for regulating ecological processes for the enhancement of the ecosystem carrying capacity

530. Paradigm shift (Zalewski 2015)

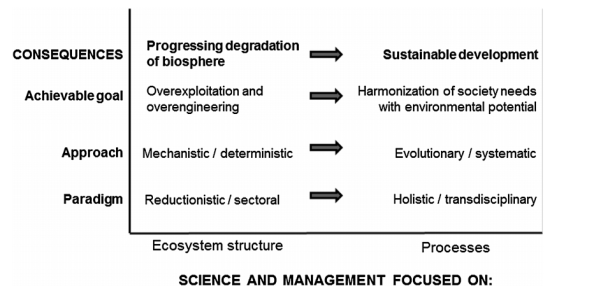

Expected direction of a shift in environmental science paradigm from the currently prevailing structure-oriented paradigm (conservation and restoration actions, focused on the assessment of the effect of various human activities on biota) to process-oriented approach (regulation of ecosystem processes, i.e., circulation of water and nutrients, and energy flow) to create a background for harmonization of societal needs with ecosystem potential, and ultimately the sustainable development; the arrows represent the expected shift in the paradigm at three levels, as follows: (1) scientific, (2) operational/practical, (3) political, and the expected results.

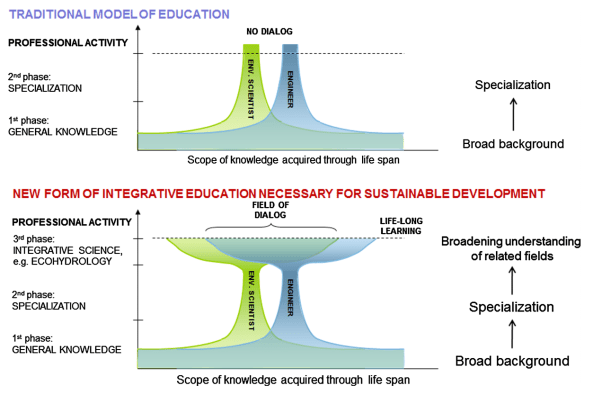

531. Integrative Science (Zalewski 2015)

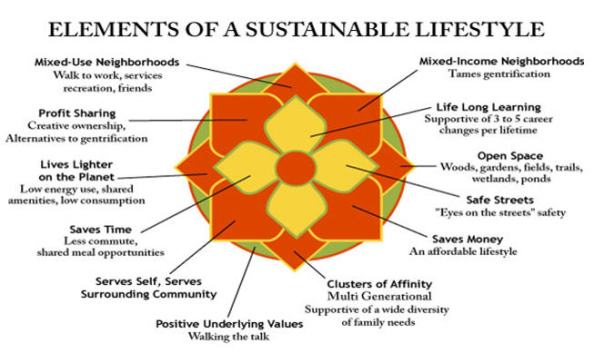

532. Elements of a sustainable lifestyle (Skeele, Beyond Suburbia 2011)

533. Spearheads (Sitra, Finnish Government 2017)

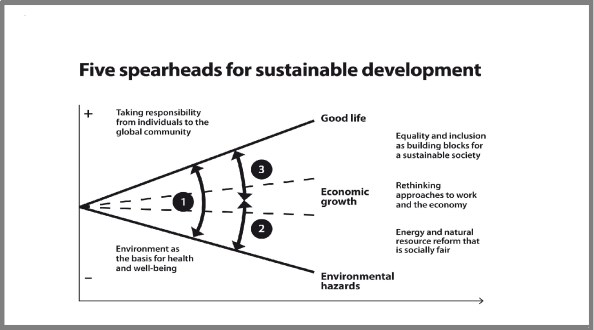

When the environment is seen as the basis for comprehensive well-being, we can live a better life at the same time as environmental hazards decline (1, see picture). In order to keep development within the ecological limits of the planet or to reverse changes that have already exceeded planetary boundaries, environmental hazards must be reduced independently from potential economic growth (2, see picture). In order to make this happen, we need an energy and natural resources reform that is socially fair. In addition, the dependence of well-being on economic growth must also be reduced (3, see picture). This is why we need to renew ways of achieving equality and inclusion, so that they can be used as building blocks for a sustainable society in the future.

Realising the three levels of decoupling described above requires a rethinking of our approach to the economy, where the economy is seen as a means of producing sustainable well-being instead of an intrinsic goal. However, none of the objectives

described here can be realised unless we take responsibility at all levels, from the individual to the global community.

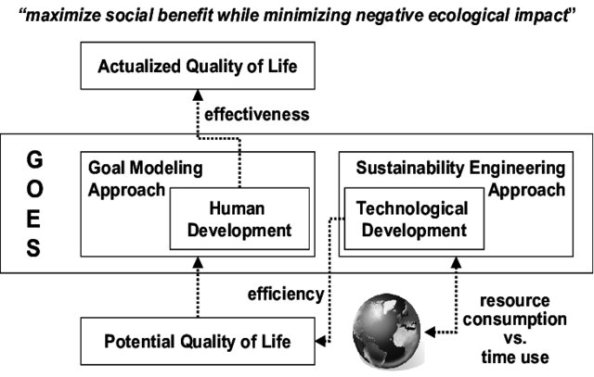

534. Goal-Oriented Engineering for Sustainability. (Mussbacher and Nuttall 2014)

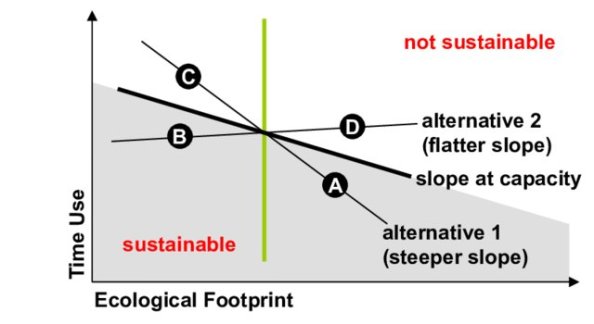

535. Sustainability Assessment Based on Slope at Capacity. (Mussbacher and Nuttall 2014)

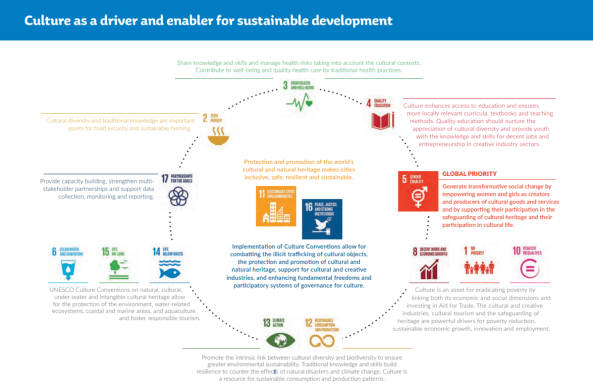

536. Culture as a driver (UNESCAP)

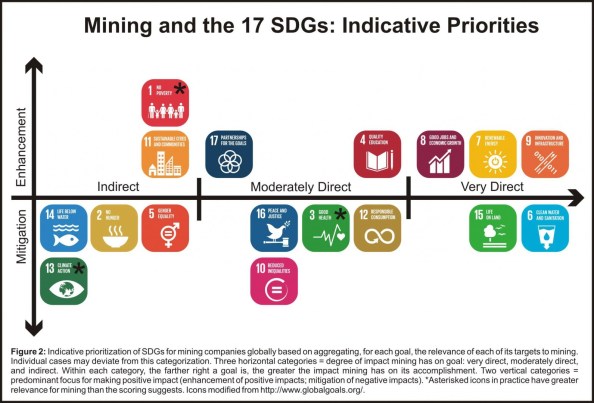

537. Mitigation and enhancement (and mining) (Davidson, WEF 2015)

The report identifies where mining can enhance the positive impacts it has and mitigate the negative impacts across the 17 SDGs (see figure1 below). For example, in addition to focusing on energy efficiency, mining companies can leverage their energy demand to extend power to undersupplied areas through partnerships that enable shared use energy infrastructure, helping to achieve SDG7 (Energy Access and Sustainability).

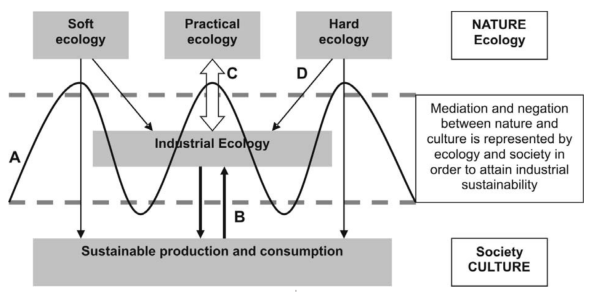

538. The new Prince (Hermansen 2006)

The model shows how industrial ecology is a construction between what is ecologically possible within the framework of the capacity of the ecosystems (biosphere) and what is socially desirable and acceptable within the framework of a sustainable society. Curve A represents connections between concern, ethical involvement and wishes for a new way of solving problems based on a holistic approach, which gives motivation and justification for implementing new industrial strategies (B). In order to manage this new challenge and to connect the problem solving to real life situation the connection between practical ecology and industrial ecology (C) must be made explicit. Support of new scientific knowledge comes along arrow D. The new ‘Prince’ is the individual, assembly, techno-structure, nations or collective that may place themselves in the central box ‘Industrial ecology’ and run the meandering and negotiation process.

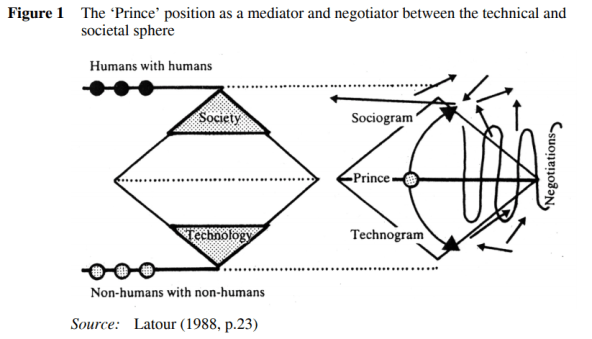

Where the new Prince is the mediator between technical and social.

Figure 1 shows Latour’s diagram of the false duplicity to the left and a more realistic one to the right. His main point is that we have to place ourselves in the new ‘Prince’s’ position and by meandering between the human sphere and non-human sphere.

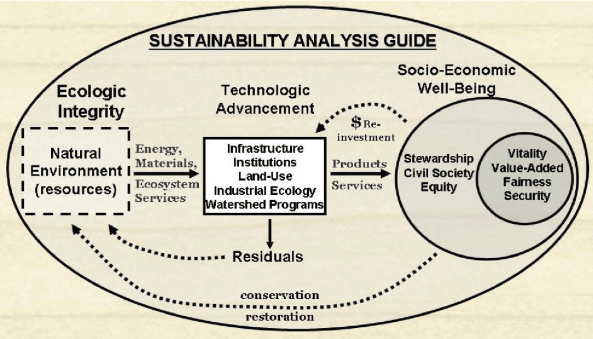

539. Technology central but won’t “save the day” (Flint 2010)

The symbolism shown here provides a thought process and guide to sustainability analysis in reference to the application of technology as a means to utilize natural resources for socio-economic well-being. Numerous feedback paths suggested by this symbolism are the source of sustainable actions for human improvement.

540. Integral Accounting (Dellner 2019)

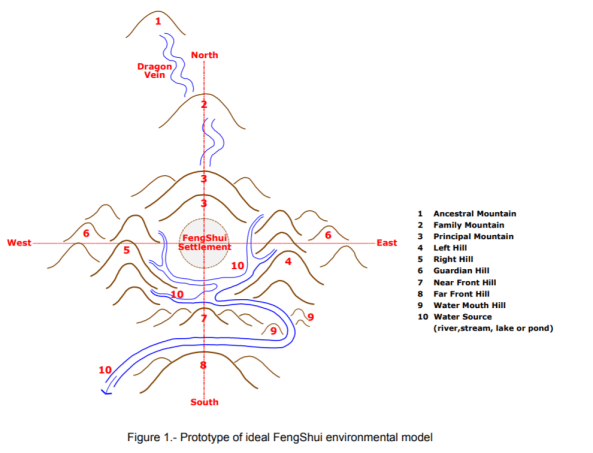

541. Fengshui (Boris Ceranic, Zm Zhong 2007)

The natural landscape located at the edge of a FengShui settlement is believed to be full of living Qi that is beneficial to local inhabitants. Through the connection and merge between mountains, water and forest, the living Qi supplies vital energy for the existence and promotion of a whole village both under the ground and on the surface of land. The flow of river, the accumulation of water (such as lake and pond) and the exuberance of FengShui forest all indicate the quality and condition of the living Qi. With the mountain to mountain, water to water and forest to forest, concealed local energy links with the national energy (Dragon Qi of royal family), interactive and complementary to each other, which enables local settlement to receive continuous living Qi from the heart of the nation. Therefore, keeping the environmental quality of local settlement and fully respecting the inherent pattern of surrounding landscape is not only a necessary approach to provide constant protection of Qi and ensure prosperity of the whole nation, but also a necessary condition to maintain the long existence of the whole community

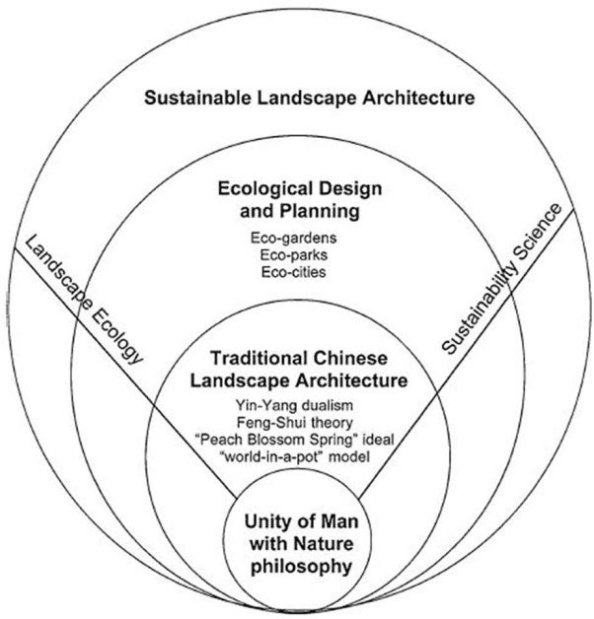

542. Sustainable Chinese Landscape Architecture (Uwajeh and Ezennia 2018)

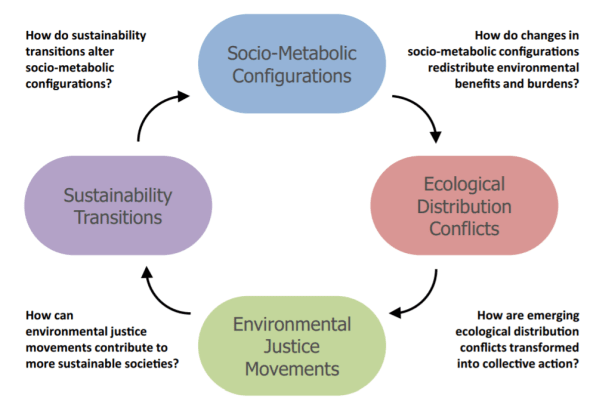

543. Ecological distribution conflicts (Schiedel 2018)

Schematic overview and key questions to understand interactions between socio-etabolic configurations, ecological distribution conflicts, environmental justice movements, and sustainability transitions.

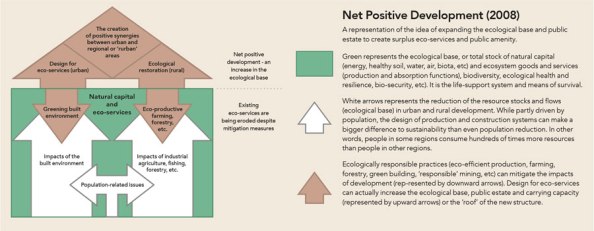

544. Net positive development (Birkeland 2008)

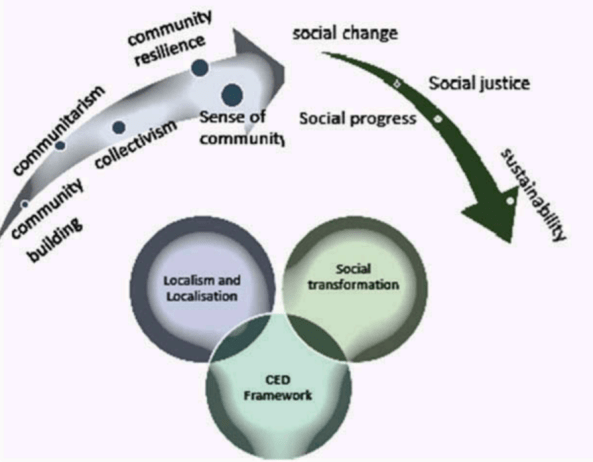

545. Community economic development (Ndaguba & Hanyane 2018)

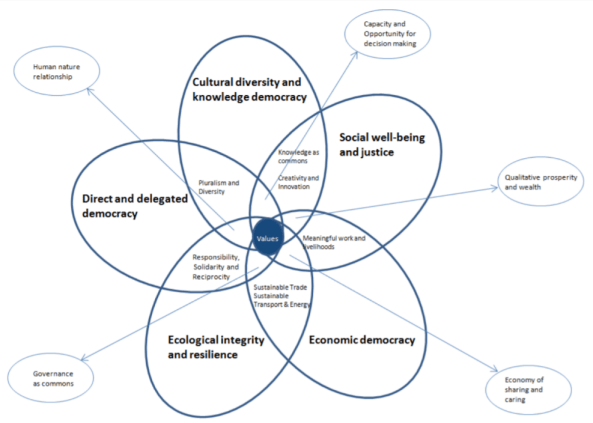

546. Eco-swaraj: Towards a Radical Ecological Democracy (Kothari 2018)

One such framework that has emerged from grassroots experience in India, with significant global resonance, is eco-swaraj. The term swaraj, simplistically translated as self-rule, stems from ancient Indian notions and practices of people being involved in decision-making in local assemblies. It became popular during India’s Independence struggle against the British colonial power, but it is important to realize that it means much more than simply “national independence.” In many of M.K. Gandhi’s writings,6 in particular Hind Swaraj, he noted that swaraj encompassed individual to community to human autonomy and freedom, integrally linking to the ethics of responsibility towards others (including the rest of nature), and to the spiritual deepening necessary for self-restrained and ethically just behavior.

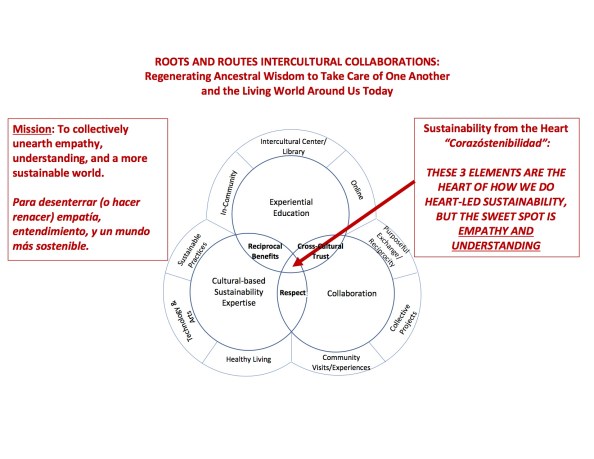

547. Corazóstenibilidad: Sustainability from the heart (Roots and Routes)

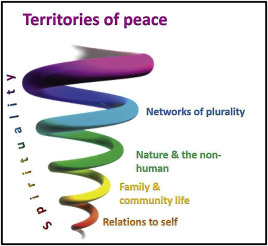

548. Territories of peace (Chaves 2018)

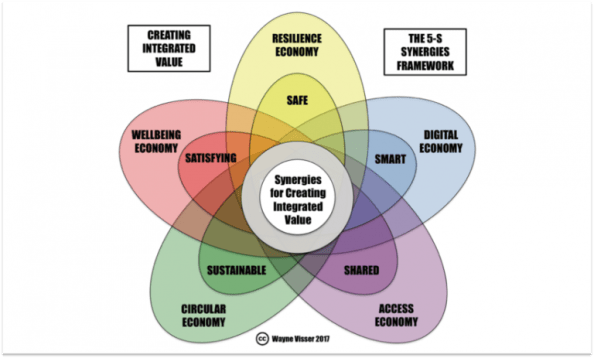

549. 5-S Synergies for Creating Integrated Value Framework (Visser 2017)

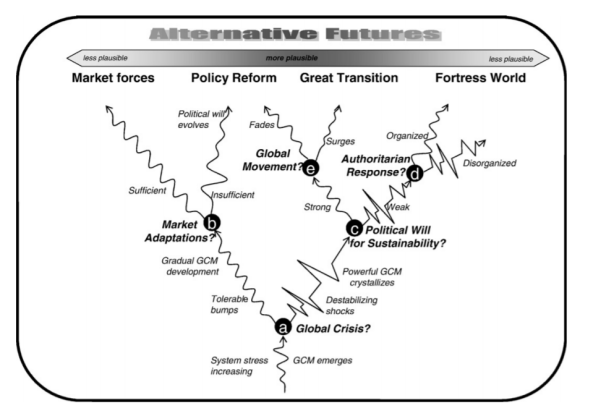

550. World lines. Alternative futures (under strong responses) (Raskin 2008)

551. Andean cosmos (Rist, in van Wijk 2010)

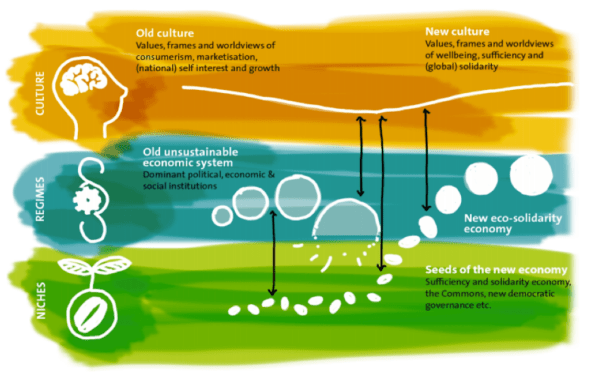

552. Re:imagining change (Smart CSO Re:imagining Activism)

If we want to change the system, trying to convince the incumbent system players (Regimes) to fundamentally change is often futile

For systems change, we need to work at multiple levels at the

same time (Culture, Regimes and Niches).Activists, organisations and campaigns need to learn how to

shift societal values and framesPioneers are building the new system. They require our support

Instead of playing the game of politics, we need to use windows

of opportunity in the old system to advance system change.We need to learn how to create positive feedback loops between

the three levels

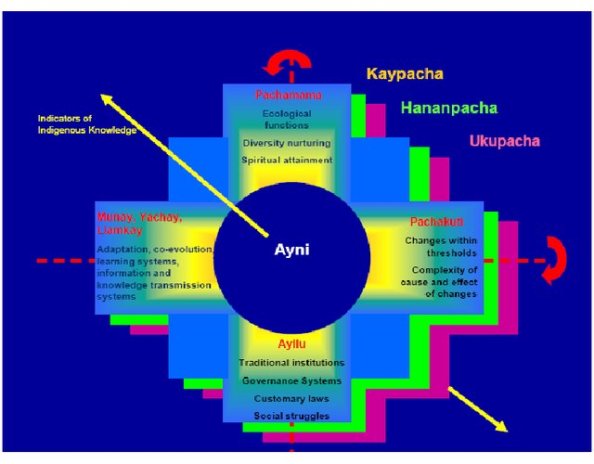

553. Vilcanota conceptual framework (Apgar 2009)

The Chakana cross figure used in the Vilcanota conceptual framework is sacred to the Quechua peoples and provided an appropriate pattern to illustrate how order in the world is shaped by collective processes based on the principle of reciprocity (Ayni) that runs across the Kaypacha, Hananpacha and Ukupacha scales. The scales represent both time and space and allow the past and future to come together in understanding. Ecosystems and their interactions with humans are understood through the four dimensions of the cross; the cyclical nature of all processes (Pachakuti), an interconnected system of nature and people (Pachamama), collective social processes (Ayllu), and learning through love (Munay) and work (Llankay) achieving higher state of knowledge about the system (Yachay)

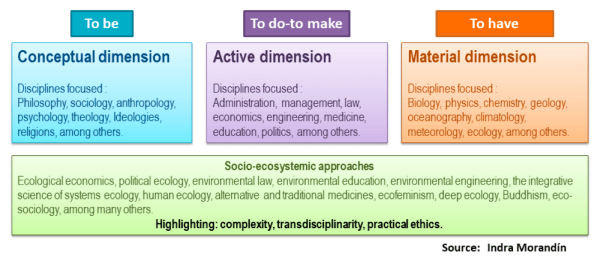

554. Socio–Ecosystemic Sustainability (Morandín-Ahuerma 2019)

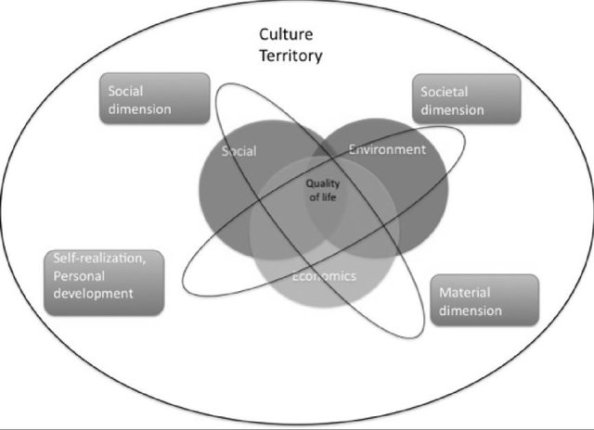

Graphic representation of the socio–ecosystem sustainability dimensions. Culture is framed by the biosphere, in which three dimensions converge: Conceptual, active, and material, in which the space–time phenomenology is presented.

555. Buen vivir (txt Walsh 2017)

In its most general sense, buen vivir denotes, organizes, and constructs a system of knowledge and living based on the communion of humans and nature and on the spatial-temporal-harmonious totality of existence. That is, on the necessary interrelation of beings, knowledges, logics,

and rationalities of thought, action, existence,

and living.

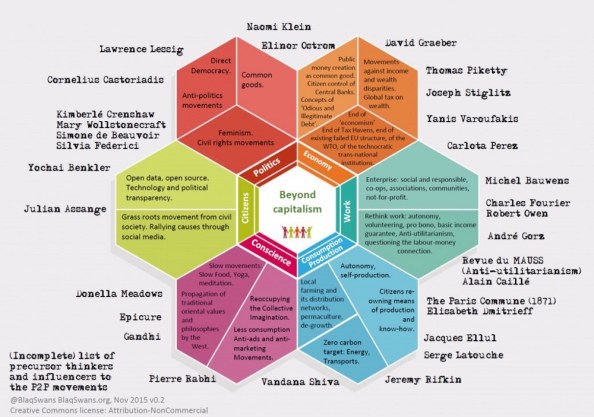

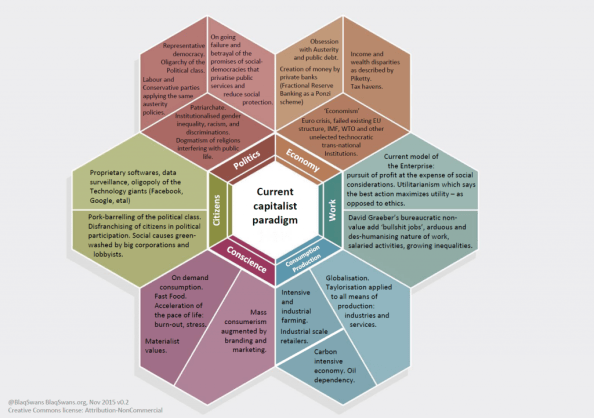

556. Thinkers beyond Capitalism (Blaqswans)

cf Capitalist

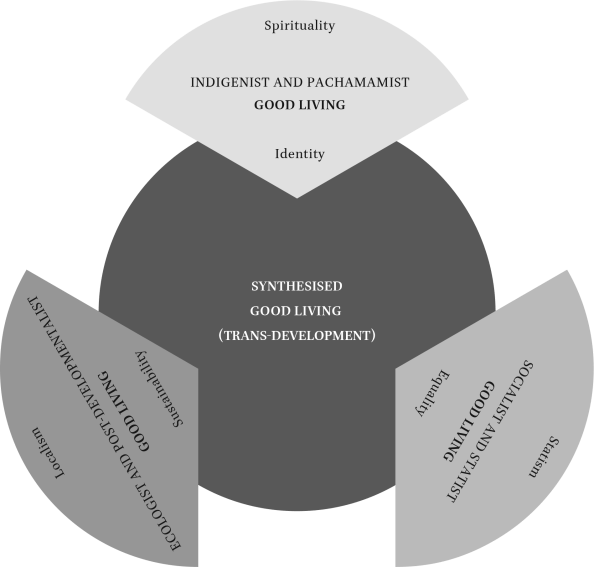

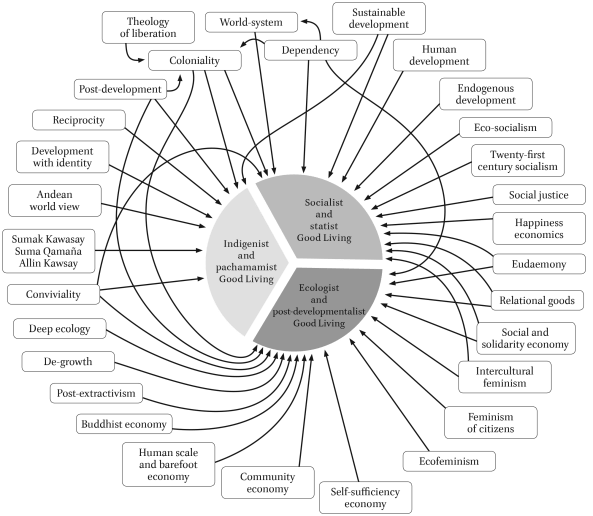

557. Trinity of Latin American Good Living (Hidalgo-Capitán and Cubillo-Guevara 2017)

Good Living can be defined as a way of living in harmony with oneself (identity), with society (equity) and with nature (sustainability) (Hidalgo-Capitán and Cubillo-Guevara, 2015).

…from a ‘de-constructivist’ perspective (Derrida, 1967), we contend that there are at least three ways of understanding Good Living —one ‘indigenist’ and ‘pachamamist’ (which prioritises identity as an objective), one which is socialist and statist (which prioritises equity) and another which is ‘ecologist’ and ‘post-developmentalist’ (which prioritises sustainability)

558. Intellectual Wellsprings of Latin American Good Living. (Hidalgo-Capitán and Cubillo-Guevara 2017)

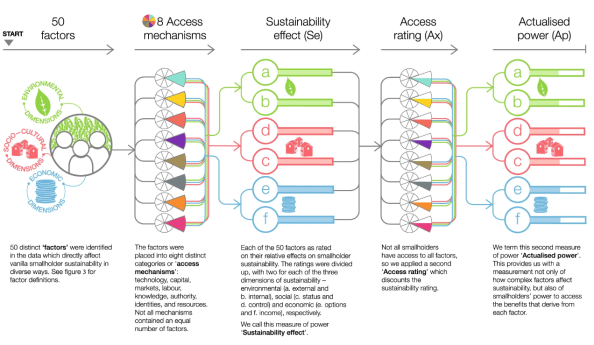

559. Access mechanisms and power to give “sustainability effect”. (Neimark 2019)

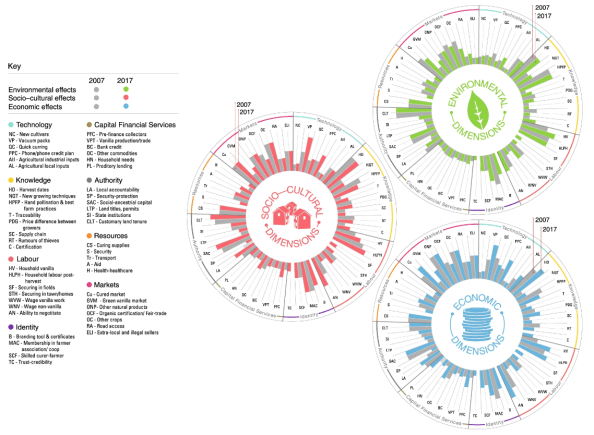

560. Synergistic pathways (IPCC 1.5 draft)

A conceptual illustration of climate-resilient development pathways, rooted in the core social dimensions 13 of human development, poverty eradication, and reducing inequalities and guided by the SDGs, while 14 climate resilience being shaped by the highest synergies and least trade-offs that emerge from adaptation 15 and mitigation pathways.

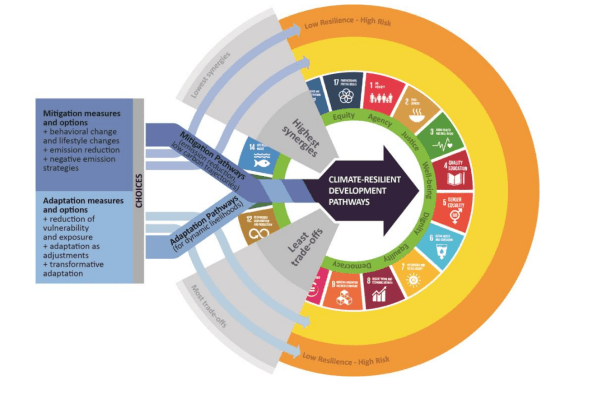

561. Triple wins (IPCC 1.5 draft)

Conceptual model of triple-wins and triple-losses. Presence of high enabling conditions affords synergies 12 between adaptation (A), mitigation (M) and sustainable development (SD) objectives, producing triple win outcomes. Increasing constrains produce fragmented responses to A, M and SD, increasing the 14 likelihood of undesirable trade-offs and triple-loss outcomes.

562. Thwinking inside a glass box (Thwink.org)

563. Brain. (Friends of the Earth Europe 2018)

No suggestion that the concepts map to these areas of the brain.

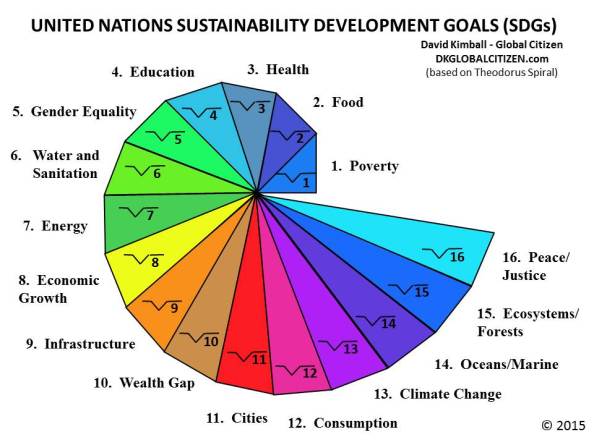

564. SDG colours on a Theodorus Spiral. Why? (Kimball 2015)

565. Sachs appeal (Sachs 2015 via Snauwaert)

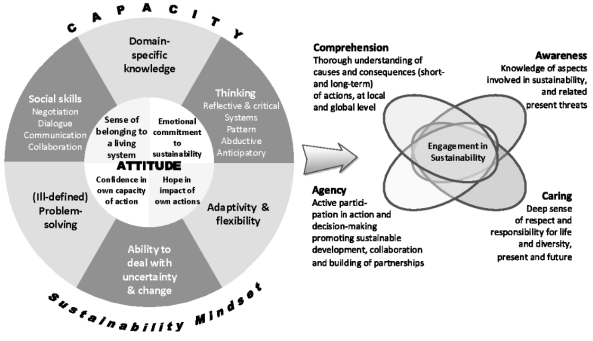

The achievement of a peaceful, just society that is socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable, is contingent upon a citizenry that possesses the capacities of complex analytic and normative thinking. Our citizenry should be afforded educational opportunities that provide them with the intellectual and moral capacities as well as the empowering political efficacy to shape the development of sustainable just peace as a matter of right.

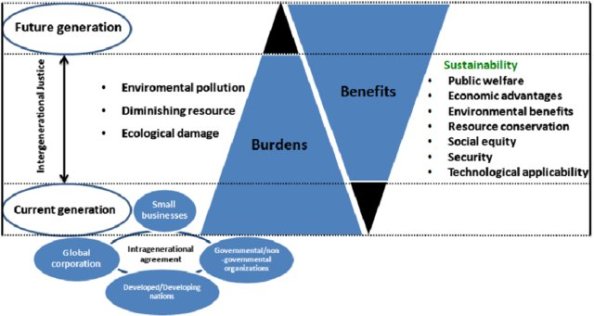

566. Equity through distributive justice in a sustainable development (Ashu Tufa 2015)

Equity through distributive justice in a sustainable development. The burdens and benefits are identified for membrane based processes applied for water and energy production. Intragenerational agreement is considered as a base line for the burden–balance to present and future generation in the process of sustainable development.

567. Regrettables (Shrimpton 2017)

The global food system is currently making enormous contributions to global warming and consequent ocean acidification, as well as biodiversity loss and the obesity and diabetes epidemics, to name just a few of its socially regrettable effects.

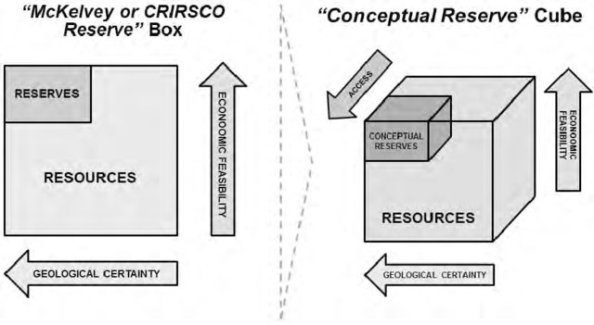

568. Conceptual Reserve Cube (Sykes 2014)

The movement from a conventional McKelvey Box (1972) to the sustainable development related ‘conceptual reserve’ cube. The former only considers geological and economic criteria, with the top left representing the most economically viable and geologically certain portion. The latter also considers sustainable development criteria through the idea of ‘accessibility’. The forward, top-left portion of the reserve cube therefore represents the most geologically certain, economically viable and easily accessible portion (source: Sykes and Trench (2014b) based on Cook and Sheath (1997), Otto and Cordes (2000) and UNECE (2013)).

579. Lots of cogs (istock)

580. Integrated Urban Planning Design and Sustainable Design Principles (Soyinka and Siu 2018)

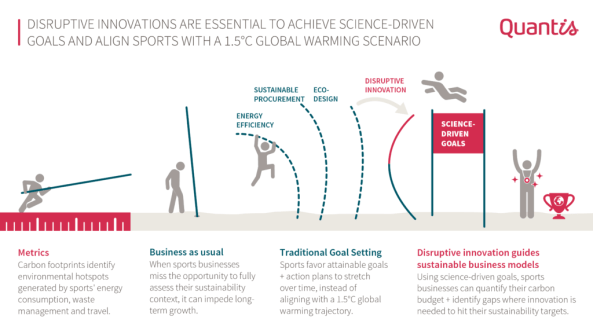

581. Pole vaulting sustainability (Quantis)

(Ok, not really a diagram)

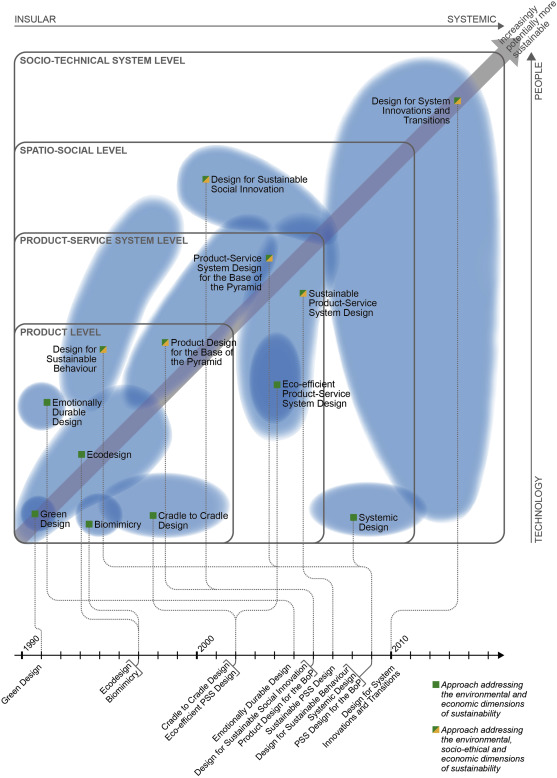

582. Design for Sustainability (Ceschin and Gaziulusoy 2016)

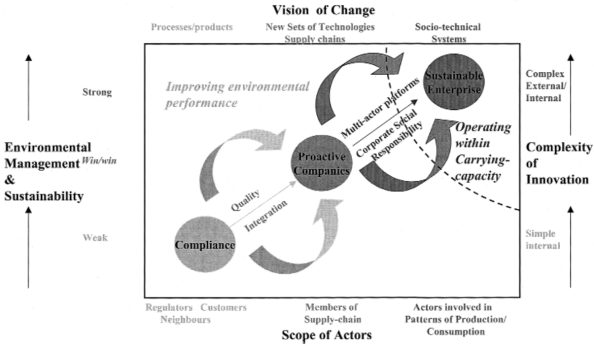

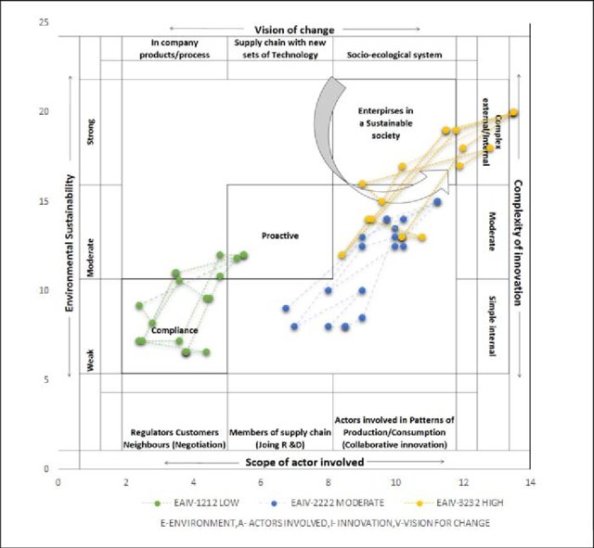

583. Weak and strong with capability maturity (Roome 2004. Toyota mapped by Basavaraj 2018)

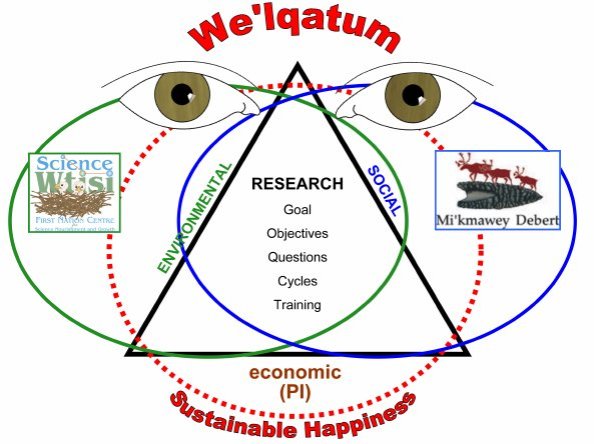

584. Sustainable happiness and we’lqatum (O’Brien 2007)

our work is housed within the three pillars of sustainability (economic, environmental and social) and will draw from both the Mi’kmaq concept of we’lqatum and sustainable happiness. The eyes in the diagram represent the Two-Eyed Seeing approach we will use. Mi’kmawey Debert and Science Wtisi are collaborators on this project. Mi’kmawey Debert is a community and land-based project to develop an interpretation centre and exhibits at the oldest directly dated archaeological site in Canada and the organization (led by the Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq) is interested in using sustainable happiness in its cultural interpretation centre. Science Witisi aims to use Two-Eyed Seeing to acquaint Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students with the lessons that can be learned from the land.

585. Efficient frontier (Imperial College Engineering)

586. Sustainability Diamond (Kammerl 2017)

However, these three dimensions are not enough for a differentiated assessment of sustainability of products. Therefore the dimensions will be extended at the level of criteria. Related to the application assessment of sustainability of products in each case at the intersection of two dimensions another criterion is introduced. Result is a

six-membered scheme with the criteria (I) ecological compatibility, (II) risk and use

effects, (III) social compatibility, (IV) national economic benefit and usability,

(V) economic profitability and (VI) resources and lifetime. The concept of the

sustainability diamond intends to open the level of criteria for a weighting by actors,

i.e. product engineer, product designer or manager.

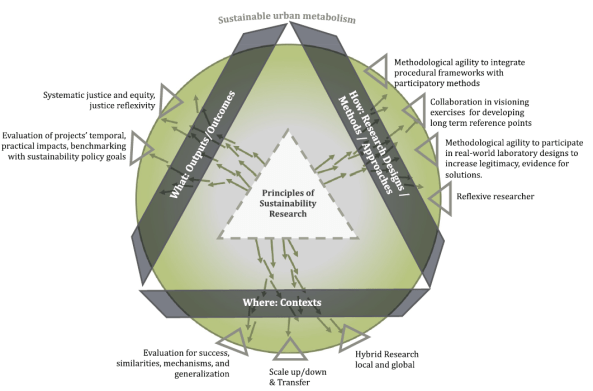

587. Pathways to realise research (John 2019)

Pathways (rep. by arrows) to realize sustainability research principles (dotted triangle) through the areas of how, where, and what (edges) within the field of

urban metabolism research (circle).

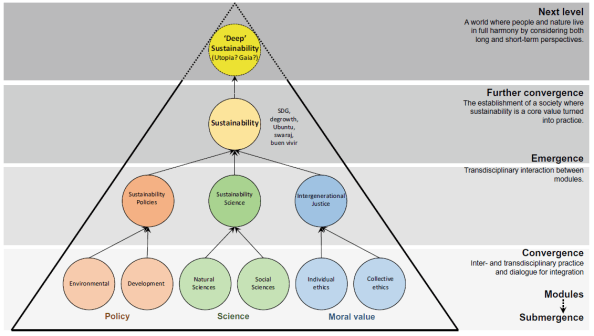

588. Emergence of Sustainability (Scarano 2019)

Schematic representation of the emergence of sustainability. The integration and convergence of distinct modules related to science, policy and moral values, resulted in the emergence of sustainability. These original modules are to some extent experiencing submergence. Sustainability, however, requires further convergence of modules—including principles, values and practices belonging to different worldviews (e.g. African Ubuntu, Andean Buen Vivir and Asian Swaraj, alongside with SDG—Sustainable Development Goals, and degrowth)—for becoming a new ‘normal’. This new state of things is a new utopia, open in format and definition. The main principle of Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis, of the biosphere in the planet interacting as an indivisible whole, is an example of the need of individually and collectively developing a new mindset to achieve sustainability goals.

589. Trilemma framework (Glover 2016)

We did not want to make a prior assumption that such a trade-off must exist among the three development goals of reducing inequalities, accelerating sustainability and building more inclusive and secure societies, yet we wanted a structure that would draw out tensions, conflicts and trade-offs between these goals, if they existed. Indeed, a key part of our purpose was to test the complacent assumption that sustainable development strategies must be mutually compatible and harmonious.

Figure 3 illustrates the trilemma framework we used and highlights some of its key characteristics. The shaded triangle illustrates the basic interaction among the goals of equality, sustainability, and security/inclusion. Each corner of the triangle is in a direct relationship with the other two corners. A given situation or scenario might be interpreted as being situated somewhere within the shaded zone but, as emphasised by Shell in their treatment of the trilemma triangle, potentially closer to one or two of the poles than the other(s).

590. Grounded sustainable cartography (Thomas 2016)

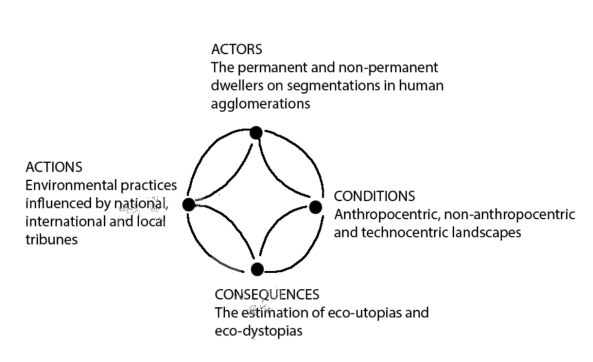

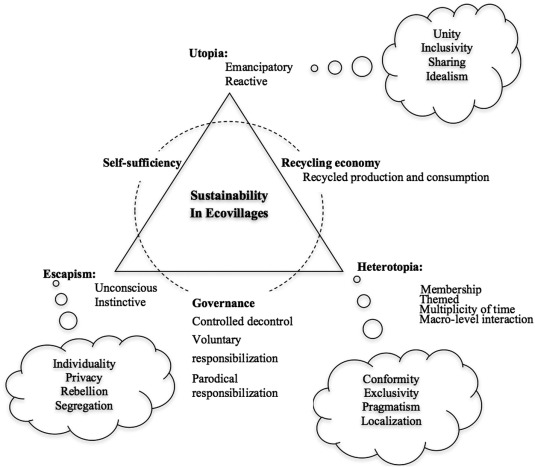

591. In the space between utopia, escapism and heterotopia (Hong 2016)

592. Spirally utopia (Sentíes and Rojo 2000 after Toledo 1997, in Heald 2012)

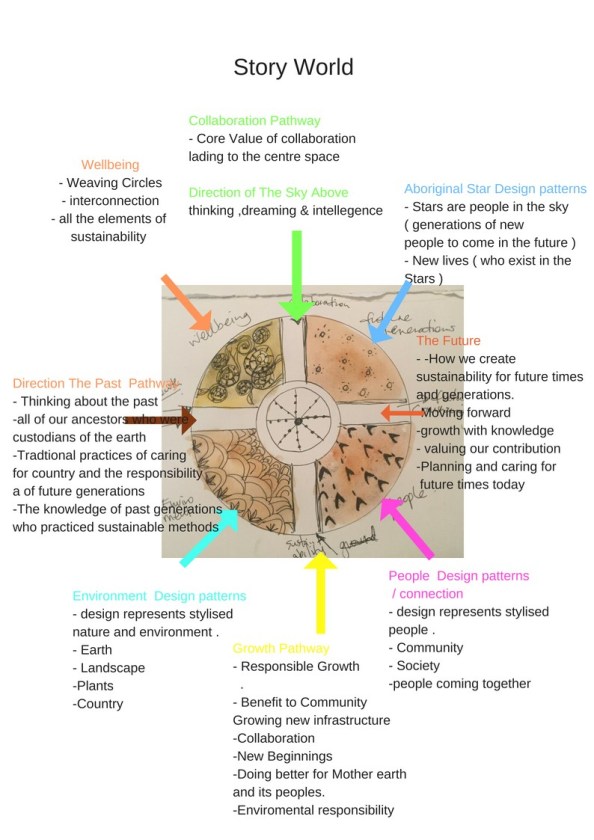

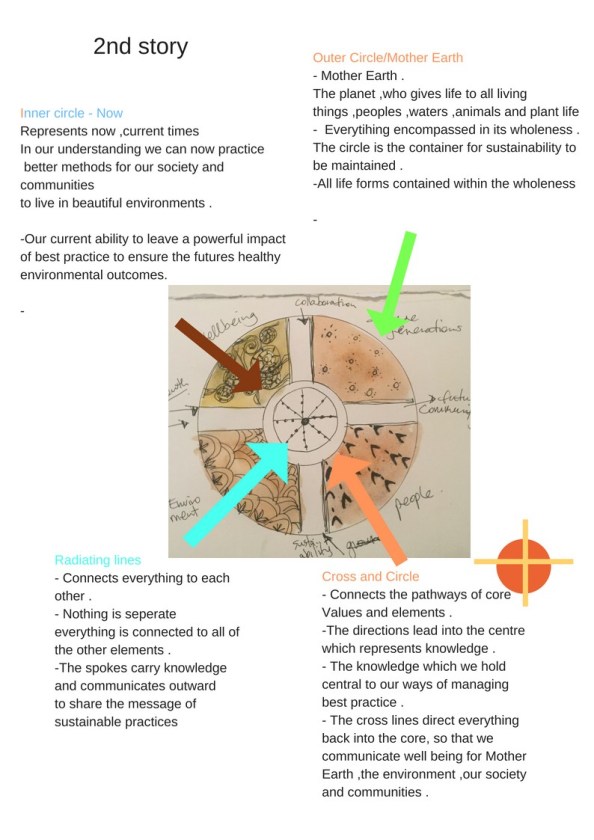

593. Story Map (Nadeena Dixo, ISCA)

594. Game affordances (Fabricatore and López 2014)

595. Cultures of Repair (Schultz 2017)

Four key threads…discussed below as concealment; newness; techne; and care. In relation to the third research question there presents a gap in knowledge for a visualisation, to read in conjunction with these threads, therefore the ‘Cultures of Repair Relational Map’ (Fig. 1) has been designed. The aim of the map is to assist designers comprehension of the gathering of modernity/coloniality and its arrival in futures (Fig. 1. part A) in order to be in a position to amplify sustainable activities in repair cultures through decolonial design.

596. Plan, Do, Check, Act. (Expressworks)

(though I’m not sure what the difference is between “do” and “act”)

597. Savoir-être and a immaterial/measurable yin/yan (Wiseholding)

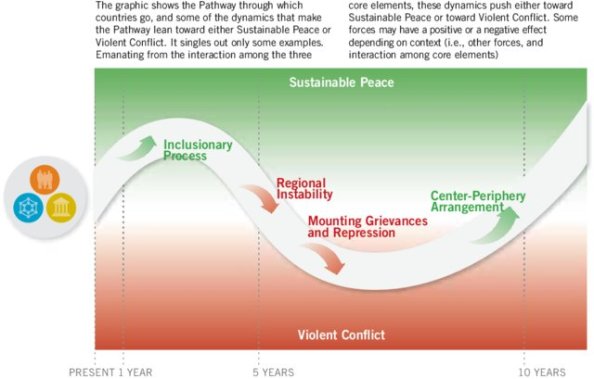

598. Sustainable Peace (Celiku 2017)

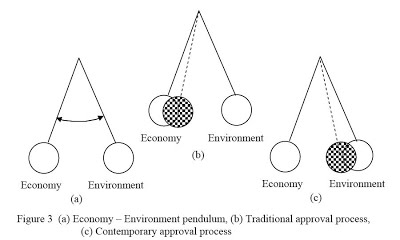

599. Pendulum (Kamphuis)

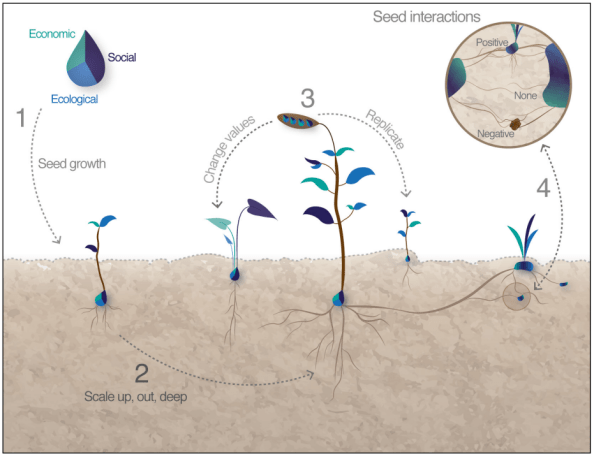

600. Seeds of a good anthropocene (Bennett et al. 2016)

(1) Initiatives, alone or in combination, that improve social, ecological, or economic dynamics within a particular setting arise and grow and (2) begin to have transformative impacts beyond initial localities and sectors as they spread. (3) Seeds may be replicated or otherwise influence existing values. (4) Importantly, the emergent attributes of those seeds, or interactions between seeds, influence the development of further innovations, spawning next-generation seeds that may have different characteristics than those of the original seed.

Posted on August 20, 2019

0